- Asset managers broadly welcome International Sustainability Standards Board’s draft reporting standards proposals on sustainability…

- …However, analysis reveals they are split on key issues such as Scope 3 emissions reporting, with a handful arguing for limited or deferred disclosure.

- The EU is more focused on sustainability than the US, which is why European asset managers are more likely to acquiesce on stricter rules.

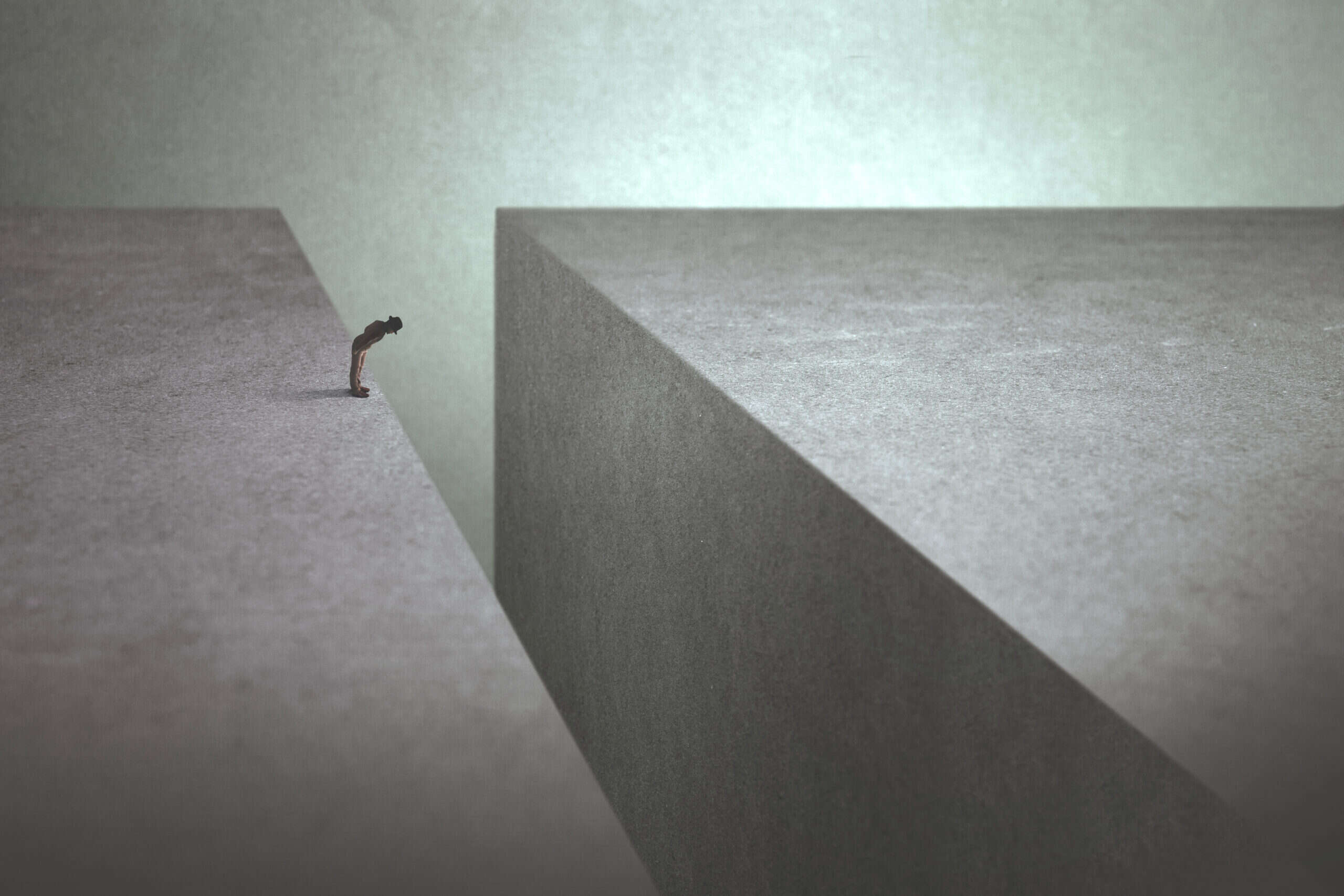

Asset managers are torn. Key sustainable disclosure issues, including whether it should be mandatory to report on Scope 3 emissions, are dividing some of the globally most influential investors, according to a recent report published by Morningstar.

The report assesses the responses of a cross-section of 20 asset managers representing more than $40trn of AUM to the International Sustainability Standards Board’s (ISSB) consultation on two exposure drafts focused on the creation of a global sustainability reporting framework. The consultation concluded in July this year.

While 40% of those surveyed prefer the ISSB to require all companies to disclose their Scope 1, 2 and 3 emissions, seven asset managers, including two of the most prominent, BlackRock and Vanguard, believe Scope 3 emissions – activities from assets not owned or controlled by the reporting organisation – disclosures should remain limited or deferred.

Part of the International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS), the ISSB is a standard-setting board focused on sustainable disclosure. The ISSB’s proposals, which broadly have the backing of many governments across the globe, are eagerly anticipated by investors who have grown increasingly frustrated by inconsistent existing disclosure standards.

The first exposure draft is IFRS S1. It proposes companies disclose information about all of their ‘significant’ sustainability-related risks and opportunities, such as on employment practices. The second, IFRS S2, focuses solely on climate-related risks and opportunities, incorporating the recommendations of the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD). This would include a company’s greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, for example.

According to Morningstar’s analysis, every asset manager either “supports” or “welcomes” the ISSB’s efforts in establishing a global standard.

However, they were not unanimous in their support of two key areas included within the drafts – namely, requirements on Scope 1, 2 and 3 reporting, and the thorny issue of materiality, the impact a company has on the world and vice versa.

Unpacking their differing stances on such crucial areas of sustainability illuminates the “ethos underlying asset managers’ approaches to ESG”, says Lindsey Stewart, report author and director of investment stewardship research at Morningstar.

The data also exposes a regional bias to both materiality and Scope 3 emissions, with an anti-Scope 3 lilt from US managers. The ISSB will have its work cut out in establishing a single, universal standard which complies with EU and US regulation.

Flexibility on Scope 3?

Seven out of the 16 asset managers that responded, including BlackRock, DWS, Invesco and PGIM, believe all companies should be required to report on Scope 1 and 2 emissions, with limited or deferred requirements for Scope 3 emissions.

The ISSB proposes that users apply the GHG protocol to measure emissions, which includes emissions from investments.

As Capital Monitor has previously reported, investors’ failure to disclose their financed emissions appears to run counter to stated net-zero aspirations, considering the majority of their emissions lie within their portfolio companies (financed emissions).

Analysing the 2030 targets of 83 members of the Net Zero Asset Managers initiative (NZAMi), Capital Monitor found that only nine have set themselves decarbonisation targets that include their financed Scope 3 emissions, while 27 reference including just some, or ‘material’ Scope 3 emissions in their target.

None of the nine were included in Morningstar’s assessment, which focuses on asset managers with larger AUMs. However, as the chart below shows, those asset managers currently excluding the Scope 3 emissions data of their portfolio companies from their interim targets are more likely to be among those requesting the ISSB exclude Scope 3 emissions from its reporting requirements, such as Vanguard.

Broadly speaking, asset managers advocating for the ISSB to exclude Scope 3 emissions do so on the grounds there is a lack of available data to work with. There are 15 sub-categories of disclosure that fit under Scope 3 reporting.

For example, Blackrock, whose 2030 target excludes Scope 3 emissions, told the ISSB: “Our investors believe the usefulness of this disclosure varies significantly right now across industries and Scope 3 emissions categories. We encourage regulators to adopt a disclosure framework that accounts for this significant variation.”

BlackRock notes that under the ISSB’s framework, “companies would disclose emissions estimates for any of the fifteen Scope 3 categories that are material to them”.

On the flip side, Wellington Management ($1.43trn AUM) which partially includes the Scope 3 emissions of its portfolio companies in its NZAMi interim target, argues that Scope 1 and Scope 2 emissions disclosure alone does not provide a complete picture to assess transition risk.

A material divide

Another dividing line is materiality. To disclose sustainability data material to the company itself is referred to as enterprise value or single materiality. To disclose the company’s impact on the world also is called double materiality. A dynamic approach refers to the understanding that what may not be relevant to investors currently in terms of magnitude or likelihood of an event can change over time.

Currently, the ISSB is leaning towards a single-materiality approach.

Speaking to Capital Monitor in May this year, Sue Lloyd, vice chair of the ISSB, explains: “We’re interested in impacts insofar as they affect enterprise value – and it’s often the case that when there is an impact [of the company on the environment] it does affect enterprise value.”

As is evident in the chart below, US-based asset managers have tended to opt for less strict disclosure rules in both cases.

This is largely down to the fact that in the EU, sustainability disclosures tend to be more detailed, whereas in the US, particularly in light of the current political backlash against ESG, there is less of a focus on sustainability.

A crowded space

As a global reporting standard, the ISSB currently sits somewhere between two other major sustainability reporting standards, whose consultation processes also closed in the summer this year.

In the US, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) has proposed rules that would require both foreign and domestic registrants to disclose climate-related information in their SEC filings alongside financial disclosures.

In the EU, the European Financial Reporting Advisory Group (Efrag) proposed its European Sustainability Reporting Standards. This is a key provision of the EU Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) and applies to all “large” EU companies, listed SMEs with a revenue of more than €20m, and non-EU companies operating in EU markets with a turnover of more than €150m.

Notably, Efrag is alone in incorporating double materiality, while the SEC is alone in only requiring Scope 3 disclosures if financially material, or where a company has set Scope 3 reduction targets.

On this, certain asset managers are outspoken. Germany’s Allianz Group, for example, argues the focus on enterprise value rather than double materiality risks creating a “significant gap between the ISSB’s global baseline and the EU’s ambition”. It adds: “ISSB and Efrag should urgently develop a collaboration model that enables global alignment and connect Efrag’s work with the ISSB’s agenda.”

“The key risk for the ISSB is that they’ve gone for the enterprise value approach, which is not quite aligned with the European Commission's double materiality approach,” says Stewart. As the European Commission is the regulator, rather than just the standard setter, “they’re going to have to find the solutions”.

But with asset managers currently standing steadfast in their views on these key areas, there appears to be no easy solution in sight.