- Despite relatively high climate policy scores, many banks increased fossil fuel funding in 2020, notably BNP Paribas and UniCredit.

- High scores can be obtained in areas where banks have historically low financial exposure.

- The results could be linked to transition finance, but greater transparency is needed.

With the recent release of the Rainforest Action Network’s (RAN) annual Banking on Climate Chaos report, it has become abundantly clear that many influential banks are not reducing their spending on fossil fuels in line with Paris Agreement principles.

The influential report digs into the activities of 60 of the world’s largest commercial and investment banks, focusing on their lending, debt underwriting and equity capital market activity. It calculates $3.8trn has gone into fossil fuels between 2016 and 2020, and flagged institutions JP Morgan Chase, Citi, Wells Fargo, Bank of America, RBC, MUFG, Barclays and Bank of China providing the bulk of that financial support.

While a great deal of focus has been on the banks’ high funding of fossil fuel majors, Capital Monitor’s analysis of RAN’s data also reveals a weak correlation between bank policy commitments and financing activity. Comparing 2019 and 2020 funding activity, it seems banks with stronger environmental policies in place are no more likely to cut financing to fossil fuels than those with weaker scores. Possibly less so.

Our analysis is based on RAN’s policy scoring system. The NGO ranks the banks with the highest spending on fossil fuels alongside the strength of the policies they have implemented for restricting their financing of fossil fuels. They are categorised across the various sectors they fund: coal mining and power, arctic oil and gas, offshore oil and gas, fracking, expansion, and liquified natural gas.

Based on RAN’s methodology, each bank will earn points based on the formal exclusion policies they have in place – the higher the score, the stronger the exclusion policy. The scoring is broken down into four sections: expansion project financing, expansion company financing, company phase-out, and company-exclusion.

At first glance, the data on banks’ spending for all sectors appears to reveal a correlation between low fossil fuel financing and strong policies – a number of those banks with the highest overall spending on fossil fuels between 2016–20, such as JP Morgan Chase and Citi, have very low policy scores, whereas banks such as UniCredit and Crédit Mutuel have both strong policies on fossil fuel financing and low financing on the industry on an absolute basis.

High policy, high exposure?

Yet while all of the largest financers of fossil fuels since 2016, apart from BNP Paribas, reduced their overall fossil fuel financing in 2020 by an average of 9%, our analysis shows that seven out of ten banks with the highest policy scores, including Société Générale, Crédit Agricole, UniCredit, Santander, Natwest, BBVA, and BNP Paribas, all increased their funding of fossil fuels in 2020 by an average of 24% compared to the previous year.

Out of the top ten banks with the strongest policies on fossil fuel expansion, which covers both oil and gas, all, apart from UniCredit and Crédit Mutuel, increased their financing of companies with fossil fuel expansion plans.

BNP Paribas in particular stands out for its 40% increase in fossil fuel financing last year (to $11.85bn), despite previously boasting of its green credentials. According to Reclaim Finance, BNP Paribas wrote to it in response to the report, arguing its increase in spending on fossil fuels was an exceptional response to the pandemic.

Either way, on an aggregate basis, the data exposes a gap between professed values and actions, where higher overall policy scores could mask high levels of financing to unsavoury sectors. Capital Monitor’s analysis raises the possibility that the policies currently in place are too weak to have any discernible impact on behaviour. After all, those banks with the strongest policies only score highly in relation to one another.

By taking a closer look at the distribution of policy scores between sectors, a connection can also be drawn between high scores for policies in sectors where individual banking institutions have low financial exposure.

For example, all of these banks scored extremely high for their policies restricting the financing of coal mining and power, but this sector makes up a minor proportion of their funding historically. In contrast, their policy scores for offshore oil and gas, the sector into which they collectively channelled most of their funding last year, are extremely low.

Transition finance

BNP Paribas, for example, also told Reclaim Finance its high increase in fossil fuel financing was with companies that had made a “critical shift” last year in relation to the energy transition.

Supporting companies that are genuinely transitioning to lower carbon-intensive activities is an important component of banking strategy, but the issue does raise the question of how far banks are prepared to interrogate the sustainability commitments of the companies they finance.

BNP Paribas was the largest financer of BP, Eni Spa and Shell since 2016, all of which are among a group of companies deemed to be not performing in line with net-zero targets by the Climate Action 100+ initiative in a recent report.

Similarly, UniCredit, despite having the strongest policies of all banks, greatly increased its funding of fossil fuels last year, including giving billions of dollars to oil majors Eni Spa, OMV AG, and Gazprom, which are also all in the Climate Action 100+ report. In fact, of all the banks, UniCredit was the largest funder of Eni Spa and the second-largest funder of Gazprom last year.

And despite being ranked seventh highest out of all banks for its policies for arctic oil and gas, UniCredit increased its funding to this sector by $514m last year, although notably, only 36 banks out of the 60 earned any policy points at all in this sector.

Digging deeper

RAN’s breakdown of the policies for each sector reveals that UniCredit earned four out of a total of 18 arctic oil and gas policy points, for its “moderate” exclusion of arctic oil and gas projects and “weak” exclusion of oil and gas companies – policies it implemented in 2019.

A “weak” bank exclusion of oil and gas companies simply means that its existing clients have to have a “plan” to get less than 25% of their revenue from onshore and offshore Arctic oil or gas, which appears to offer a large amount of leeway to those banks wanting to continue financing them while appearing to be acting in line with climate commitments.

Similarly, while BNP Paribas is one of the few banks assessed as having a “strong” exclusion policy for arctic oil and gas projects, it still managed to increase its funding to arctic oil and gas companies by 53% to $320m last year. Its policies for arctic oil and gas projects and pipelines are restricted to unconventional arctic oil and gas only.

As the RAN reports notes, a huge limitation of the banks’ policies on fossil fuel funding is that while the majority of their policies are focused on project-specific finance, only 5% of fossil fuel financing is described as being related to certain projects. This means that banks can simply fund fossil fuel majors directly, while appearing to be following restrictive policies.

If, as this data suggests, it is possible to be awarded the title of best bank for policies restricting financing of fossil fuels while continuing to increase spending on the industry, banks may take too long to reach their net-zero targets.

BNP Paribas and UniCredit did not respond to emails requesting comment on this story.

Notes

- The first chart takes bank policy scores provided by the RAN dataset given above, and shows the score for each sector as a percentage of the total points available. It shows them as a percentage rather than numbers, as while there are 18 points available for most sectors, there are 80 points available for coal policies in total. However, the number of policy points available does not reflect the number of policies. We have aggregated coal mining and coal power policy points in the first chart for the sake of visual simplicity.

- Furthermore, we break down the spending into total spending for each of the sectors shown in the second chart. We decided to omit both spending and policies on “expansion”, despite the data being provided alongside the other sectors by RAN, because “expansion” as a category includes all of the sectors, and therefore muddles our analysis of the specific sectors.

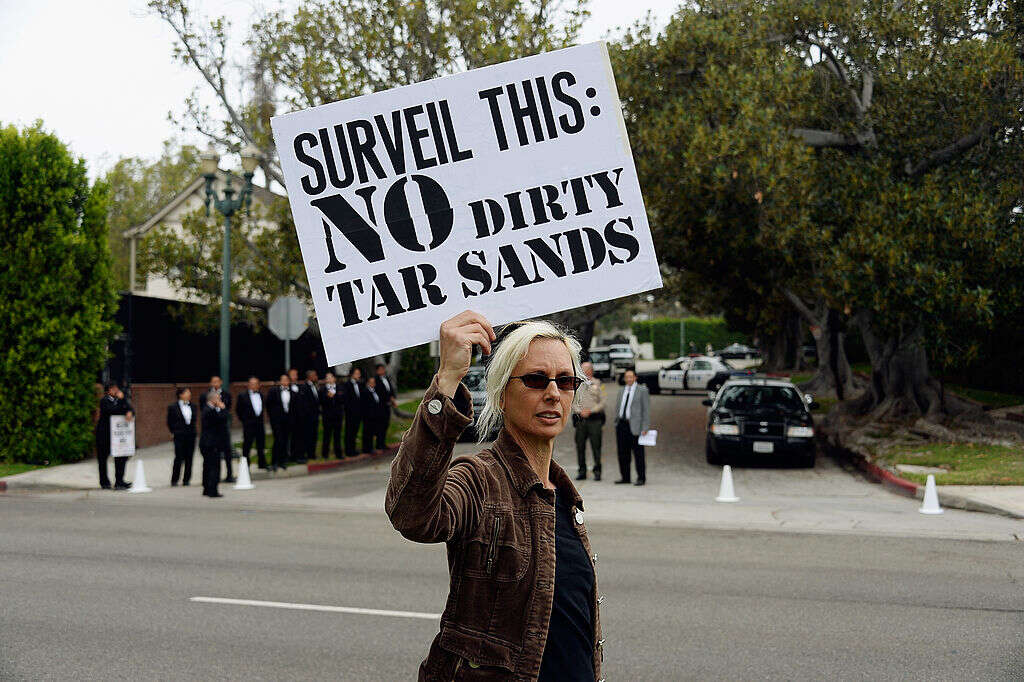

- In 2020, banks spent $113bn on financing offshore oil and gas, compared with $16bn on tar sands, $10bn on arctic oil and gas, $90bn on fracking, $25bn on coal mining, $39bn on coal power, and $29bn on liquified natural gas.