- Chinese banks are behaving like lenders of last resort to the coal sector.

- Are governments deliberately turning a blind eye to bank policies on coal?

- State-linked banks may end up holding stranded assets on their books with little consequence.

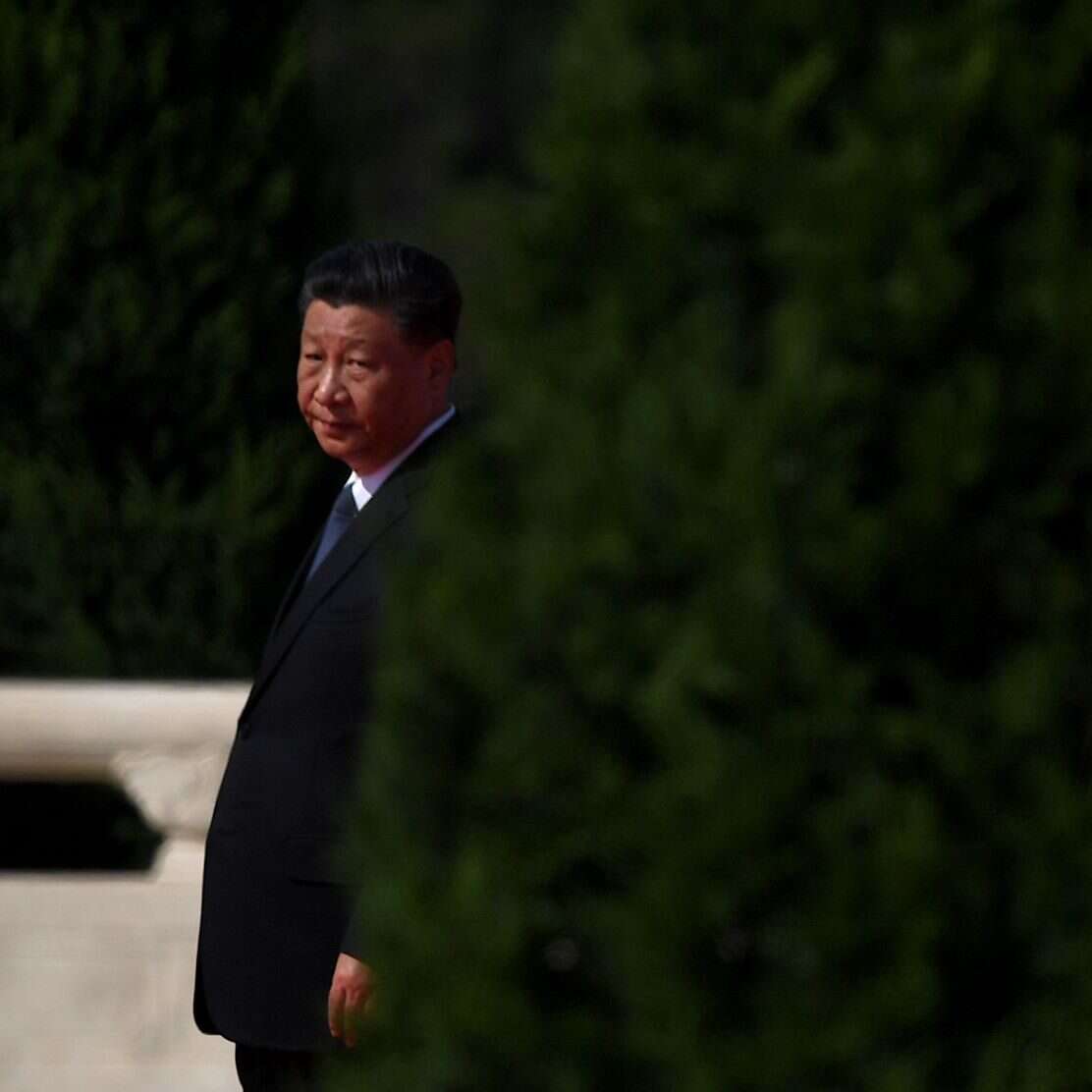

China’s new five-year economic plan is indicative of the divergent paths countries are taking to meet net-zero commitments.

Despite being hailed as a dramatic shift in climate positioning, China’s 2021–25 economic plan announced on 5 March failed to ban the production of new coal-fired power plants. This comes at a time when an increasing number of countries are looking to eliminate fossil fuels entirely from energy generation. Chinese banks are widely seen as lenders of last resort for fossil fuels, especially coal.

“With Chinese financing currently the principal option available for coal-fired power projects… we are likely to see such projects primarily being undertaken through Chinese debt and equity, and even this will likely tighten given China’s own net-zero agenda,” says John Yeap, a Hong Kong-based project finance specialist at Pinsent Masons.

But power plants built today are likely to still be operating beyond China’s 2060 net-zero target. For many countries the transition to net zero implies dramatic cuts to greenhouse gas emissions in the near term, thus stranding assets before the end of their useful life.

Harder for hydrocarbons

In context, China looks slow to advance. Hungary recently announced that it would become coal-free by 2025, joining nine other European countries with the same vision. On point, the European Parliament called on the European Commission to introduce legislation requiring companies to find and fix environmental risks in their supply chains.

Such moves will see companies increase the pressure on suppliers to improve their practices, and firms operating in an increasing number of sub-sectors are already finding it harder to secure financing.

An analyst at an international credit rating agency notes his firm downgraded coal port operators across the board in Australia “because Australian banks are pulling away” from financing the sector. In direct contrast, state-linked utilities in countries such as Malaysia and Indonesia that still have access to domestic bank and/or government financing, and weren’t facing refinancing risks, were left alone.

But how long can this form of state support last? Savvy asset managers are now moving up and downstream when it comes to hydrocarbons. For example, the Whitehelm Listed Core Infrastructure Fund excludes assets exposed to stranded asset risk, including companies that own transport assets that are more than 10% exposed to coal, electric utilities with a significant amount of coal-generating capacity, and companies that own oil pipelines.

The strategy illustrates the shifting from excluding companies directly involved in thermal power generation to also excluding those transporting coal and oil to power plants. Some see it as only a matter of time before companies operating pipelines transporting any type of fossil fuel are also excluded, although others see some future for existing gas pipelines transporting a blend of hydrogen and natural gas.

Guiding taxonomies

On the regulatory front, the EU’s Sustainable Finance Taxonomy Regulation is due to be finalised in April, after the treatment of gas and biofuels is finalised.

While the taxonomy is about disclosure, some institutional investors are expected to adopt the taxonomy to inform their investment criteria. In addition, other institutions have produced their own taxonomies, outlining net zero-compatible activities.

In January 2021, for example, the Climate Bonds Initiative introduced traffic lights for different sub-sectors – with a red mark for sub-sectors deemed incompatible with a 2°C decarbonisation trajectory.

It won’t be government policy necessarily or a decline in volumes that strands these assets; it’s more likely to be financial triggers such as refinancing failures.

The use of oil and coal in generating power along with biofuels in transport were among activities garnering red marks. With the whole sub-sector deemed to be incompatible there is no room for identifying best-in-class companies operating in these sub-sectors, as all are tarred with the same brush.

Gas-related assets are facing increasing opposition, such as protests in March against a new gas-fired power plant proposed by Xcel Energy in Minneapolis, US. Attitudes in the country sit somewhere between those in Europe and Asia when it comes to natural gas.

A transition fuel?

Natural gas is not seen as a transition fuel in Europe, notes the credit rating analyst, but natural gas is seen as part of the transition in Asia-Pacific, he adds, “in part because coal and oil are still a big part of the energy mix – so it is harder to see banks in Asia-Pacific pull away from natural gas”.

He sees banks following government policies. Others see government policies following rather than leading.

“It won’t be government policy necessarily or a decline in volumes that strands these assets,” says one fund manager, referring to assets stranded before the end of their useful lives. “It’s more likely to be financial triggers, such as refinancing failures and an inability to insure assets. Also, investor sentiment can shift very quickly.”

Former MUFG banker Duncan Ritchie sees customers as a more potent force change, impacting company operations all around the world. This includes myriad B2B customers that make up a company’s supply chain, which are the focus of the latest initiative from the European Parliament. European companies have not had to conduct due diligence on the environmental risks posed by companies in their supply chains.

The insistence of companies on the availability of renewable energy has been a key factor driving the growth of wind and solar power in some emerging markets, which are keen to attract multinational companies.

People power

Along with B2B companies within the supply chain, end consumers are also important drivers of change. Ritchie set up Zero-Carbon 2030 last year to provide ratings based on a company’s plans to transition to net zero.

A relatively small group of customers can change a company’s behaviour, asserts Ritchie, citing the results of sensitivity analysis. A 5% loss of sales by S&P 500 companies can have a 20–50% impact on their bottom line, he says, with more capital-intensive companies being more sensitive.

Big carbon emitters in the cement, steel, iron, aluminium, chemical and glass-production sectors are relatively capital-intensive, with high fixed costs contributing to big swings in profit from relatively minor changes in sales.

Rather than risk losing sales, an increasing number of companies are adopting tougher transition plans, as tools such as the Zero-Carbon 2030 app help customers identify and then punish poor performers.

Companies like Total are working to make sure they continue to have access to bond markets. One risk is that bank financing dries up for specific activities.

Ritchie admits he has been surprised by some of the ratings his team has generated. For example, Enel received an A rating due to its sound plan to transition to net zero, despite the company still operating some coal-fired power plants.

The Italian energy company is well ahead of its peers, such as France’s Total (B+), UK-headquartered Shell (C+) and BP (C), as well as Petrochina (D).

Total’s B+ rating means it is not doing much more than complying with regulations. According to Zero-Carbon 2030’s bands, a B-rated company is a “complier”.

The company rewards those that plan to do more sooner. Total has a long-range target for reaching net zero by 2050, but interim targets between now and then are unclear.

Drying up

Companies like Total are working to make sure they continue to have access to bond markets. One risk is that bank financing dries up for specific activities.

“I think we are the first company in the world to propose to embed our transition within our financing policy,” said Total’s chairman and CEO Patrick Pouyanné during an earnings call in February. “The idea is to use climate KPI bonds in the future,” said CFO Jean-Pierre Sbraire, referring to key performance indicators (KPIs).

Meanwhile, Colin Gruending, CFO of Canada-headquartered pipeline operator Enbridge, boasted that a three-year $1bn sustainability-linked credit facility “is a first among our peers”.

“We’re excited by this financing as it links our ESG performance with our borrowing costs,” he said during a 12 February earnings call.

Gavin Smith, vice-chair of the Green Growth Sector Committee at the European Chamber of Commerce in Vietnam, observes that bank financing for coal-fired power plants is drying up. “The death knell for coal plants in South East Asia is sounding as the traditional risk-accepting agents in Korea and Japan are pulling out,” says Smith.

In a press release marking Mitsubishi Corporation’s withdrawal from the 2GW Vinh Tan 3 coal-fired power plant in Vietnam last week, Pinsent Mason’s John Yeap commented that Chinese financing is now the principal option available for coal-fired power projects.

Peer pressures

The project has been under development for more than a decade and was boosted when China Development Bank Corporation came on board in 2015, a year after HSBC was appointed financial advisor. Then, last year, Mitsubishi bought out Hong Kong utility CLP’s stake and HSBC withdrew as financial advisor.

CLP was one of the original developers of Vinh Tan 3 as well as Vung Ang 2, which it is has also withdrawn from. Smith notes that the Japan Bank for International Cooperation (JBIC) has announced that Vung Ang 2 will be its last financing of a coal-fired power plant, as “coal financing is being pushed into the risky margins, illustrated by the embarrassing involvement of a sanctioned Russian bank in another Vietnam coal plant consortium”.

“In Vietnam, complex negotiations for partial government guarantees, and land and licence problems, meant that only 50% of the fossil fuel plants in the last national plan were delivered,” observes Smith.

Given that coal-fired power plants can keep on operating for 70-odd years, the likelihood is that many being built today will be stranded. And the banks that remain active in financing fossil fuel-related projects have finite capacity.

Recently, the government of the main coal-producing province in China – Shanxi – called on financial institutions to buy regional coal firm Jinneng’s debt as the notes fall below a specified price. And while government pressure in places such as China will prove useful for now, loss-making activities are ultimately unsustainable – just like burning fossil fuels.