- Equatoria Teak in South Sudan shows how private capital can help break the cycle of poverty that persists in many conflict-affected situations.

- The company’s owner, private equity firm Maris, has had to deal with challenges unheard of by most investors to achieve lasting impact.

- Humanitarian and resilience investing is an emerging asset class championed by the World Economic Forum, Credit Suisse and others.

In Nzara, a once-industrial town in South Sudan near the border with the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), a forestry company has defied civil war to bring stability, education, healthcare and employment to an area riven by conflict.

Private equity-owned Equatoria Teak Company (ETC) is in a remote place reached only by air or unsurfaced roads running through the DRC – the latter being the only transit route for timber exports. Roadblocks, harassment and lack of power are daily challenges for drivers. But rebel groups had presented the most immediate danger, having set fire to trees and uprooted coffee plants in the vicinity.

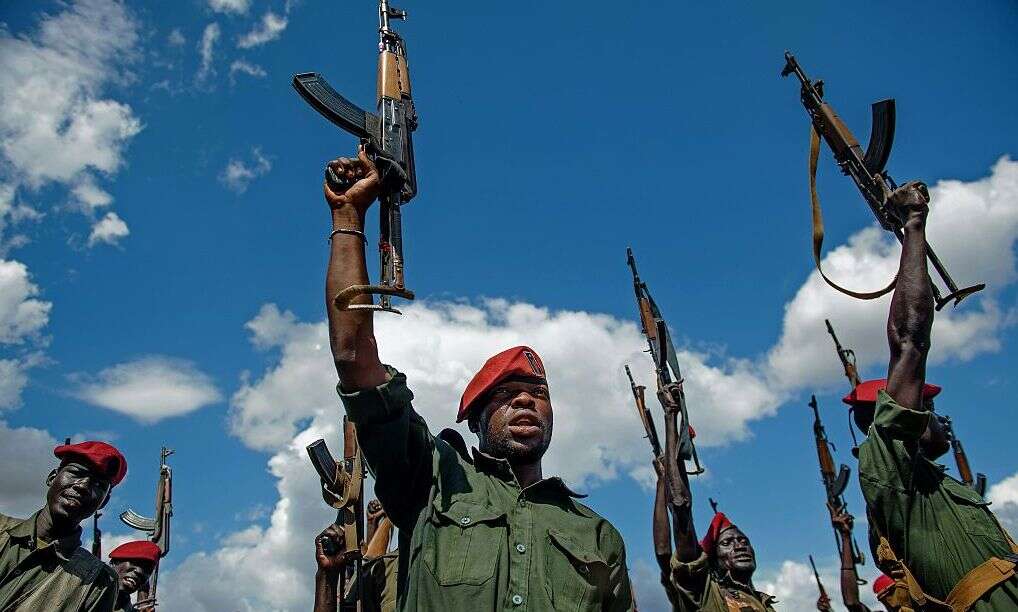

ETC, Africa’s second-largest teak grower with 2,200ha of plantation, is in a part of South Sudan that saw particularly intense fighting. Civil war has been persisting there for decades, the latest bout coming between 2013 and 2018. In 2017, local government allocated soldiers to protect company staff. But it was by employing ex-combatants, including rebels, that the company was able to secure the area, bring peace to Nzara and help the region on the way to prosperity.

These are the type of problems that can face businesses operating in such locations, which most companies never have to think about and most investors prefer to avoid.

“There are a lot of people who talk about impact, but we are delivering more impact than I have ever seen delivered in any project,” says Charlie Tryon, chief executive and founder of ETC’s owner, Maris, a pan-African private equity firm headquartered in Mauritius. He ran Neda Telecommunications in Afghanistan before setting up his current business.

Maris, which operates in 11 countries across east and southern Africa, also has holdings such as 100% of Equator Equipamentos in Mozambique, which provides services for oil and gas and construction companies, 92% of the Rungwe Avocado Company in Tanzania and 80% of the Commoner Gold Mine in Zimbabwe.

Maris aims to return a payback in cash within four years of any project if it is to consider investing, with an exit horizon of around ten years. The firm targets an internal rate of return (IRR) of 15–20% while generating a cash yield from the portfolio. By 2026 it aims to have exited most of its investments.

We created jobs for people who were combatants or ex-combatants and it brought peace and stability to an area. Charlie Tryon, Maris

Now ETC is the largest private taxpayer in Western Equatoria State and has some 1,000 employees, 90% of whom are from the local Nzara community. The company runs a community fund programme that supports healthcare services and training for its employees, and a secondary school, for which it has drawn praise from both the US Agency for International Development and local government.

“We created jobs for people who were combatants or ex-combatants and it brought peace and stability to an area,” says Tryon. “Former child soldiers and young men who were associated with rebel groups put down their guns and picked up a pruning saw or a hoe.”

The sharp end

This is the sharp end of impact investing, bringing private capital, jobs and regeneration to a part of the world that sees only a trickle of the billions of dollars of private capital now earmarked to support the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

More than 800 million people live in countries affected by what the World Bank refers to as fragility, conflict and violence (FCV). The development institution views this as a critical development challenge that threatens efforts to end extreme poverty.

South Sudan, the world’s youngest country after only gaining independence from Sudan in 2011, is also one of its most fragile. It has emerged from prolonged civil conflict with some 80% of its population living below the poverty line, according to the International Monetary Fund.

The Covid-19 pandemic has only exacerbated such issues, and the need for private capital is urgent, development professionals say. South Sudan is ranked the world’s sixth-hardest place to do business by the World Bank and sits at the bottom of Transparency International’s Corruption Index.

There is no substitute for patient groundwork in such locations. “You need to take a 25-year view with a project in a country like South Sudan,” Tryon says.

Political, security and other third-party consultants can help, but Maris builds its knowledge in-house. Regular country visits, meetings with investment authorities and the local business community help the firm “triangulate the risks and challenges of doing business there”, says Tryon.

Moreover, South Sudan’s legal system is a mix of sharia and British law, which makes it challenging to navigate. Not to mention the fact that respect and understanding of the law is limited.

Of course, things do not always go to plan. Maris liquidated an investment in South Sudan after its counterparty transferred the US dollar contract into South Sudanese pounds. “It became too risky,” Tryon says. “We couldn’t operate the business, so we wound the company down and took all the cash out.”

Reluctant capital

Unsurprisingly, then, raising private capital to invest in conflict or fragile markets is not easy. The private sector has a crucial role to play in plugging the humanitarian aid funding gap of more than $20bn, the World Economic Forum (WEF) says.

With risk appetite waning post Covid, and compliance and governance standards tightening, the issue is being exacerbated. Tryon says that when he talks to potential investors, people love the story but are rarely willing to invest.

“We’re hearing a lot about climate change, impact investing and how people can address the SDGs,” he adds. “To me, there is a lot of talk. People are trying to direct their capital into what they consider to be easy, scalable wins, which in my view deliver very little impact.”

Yet larger institutional flows that could make a meaningful difference are harder to capture in this part of the market. In 2018, the Africa Private Equity and Venture Capital Association reported the average private equity deal size as $6m–$8m.

Conflict challenges

After all, investment into fragile and conflict-affected situations (FCSs) faces major challenges. They include weak regulatory environments and legal frameworks, a lack of predictability, and security and personal risk. Fundamental change is often required right from the very top, and political instability can derail an investment project proposed even by the most experienced actors.

“You need multiple stakeholders involved – not just capital, but policymakers and governments – because they form the basis and foundations on which any investment comes from,” says Michael Sieg, CEO of Zurich-based impact investment manager ThomasLloyd.

The company turned its sights on Cambodia in 2012, making its first direct investment in April that year. Sieg says the firm was bullish about the formerly war-torn and hugely poor country’s prospects (“all the macro factors were amazing”) even though “there were many issues with bribery and corruption”.

However, after hopes for a change in government were dashed by the re-election of the Cambodia People’s Party, the firm decided to pull out. “We were hoping with new elections [Prime Minister] Hun Sen would be voted out, but the long-term PM was re-elected so we said we can’t be there.”

A rising asset class: HRI

Despite the unique challenges posed by investment in FCS states, some organisations are making efforts to scale up humanitarian and resilience investing (HRI) as an emerging asset class.

London-based GIB Asset Management is working to draw out HRI as a future investment theme, Venetia Bell, group chief sustainability officer and head of strategy, tells Capital Monitor. The firm’s partners include the WEF, Credit Suisse, the International Committee of the Red Cross, the Netherlands and the World Bank.

GIB is working to address how to transition pure philanthropic assets to ensure commercial returns.

The WEF-led HRI group’s strategy focuses on three main areas: developing early-stage projects with deep humanitarian and resilience outcomes, mainstreaming the concept of HRI and improving data collection.

By developing certain initiatives, the group seeks to attract more mainstream investment. These include H2Grow, a United Nations World Food Programme project that aims to make hydroponics affordable to help food-insecure families access fresh food and raise their incomes.

Better data collection could unlock funding for HRI strategies by mitigating financial, reputational and compliance risks, says Bell. The group advocates using digital technology, such as satellite and drone imagery, to collect data to improve the number of bankable HRI transactions.

But Bell concedes that doing so can be particularly tricky in fragile markets. “Trying to persuade people that data management matters is difficult in the context of the sort of crises they are facing,” she says.

And yet that sort of bridge-building – and way more besides – is badly needed if sufficient investor capital is to reach more conflict zones.