- Luxembourg Stock Exchange (LuxSE) is the leading bourse for green, social and sustainability (GSS) bonds, listing half the global total.

- LuxSE chief Julie Becker calls for greater harmonisation of sustainability disclosure via regulation, but is against making the green bond standard mandatory.

- GSS debt issuance is rising fast generally, with the Vienna Stock Exchange last year recording a near doubling in the number of such bonds it lists.

The growth of green, social and sustainability-linked (GSS) bonds in Europe shows no sign of abating, with exchanges helping to drive this expansion. The EU market for GSS debt stood at €1.2trn ($1.3trn) at the end of March, up 50% year-on-year, said Verena Ross, chair of the European Securities Markets Authority (Esma) at the International Capital Market Association (Icma) conference this month.

In late May, Dutch transmission system operator Tennet sold the biggest corporate green bond so far, for €3.85bn, and the number of sovereign green issues is also proliferating. At the same time, investors and bankers are becoming increasingly savvy – and, in some cases, choosy – about deals, particularly in the sustainability-linked space.

A leading contributor to the market’s growth has been the Luxembourg Stock Exchange (LuxSE), the world’s first dedicated green stock exchange. It listed the first green bond to enter the market in June 2007 (the European Investment Bank’s climate awareness bond) and in November 2008 the second (the World Bank’s first green bond).

In the aftermath of the Cop21 climate summit in Paris in December 2015, LuxSE set up the Luxembourg Green Exchange (LGX) in September 2016, after the United Nations had launched the Sustainable Stock Exchanges Initiative the previous September to contribute to the financing of development projects.

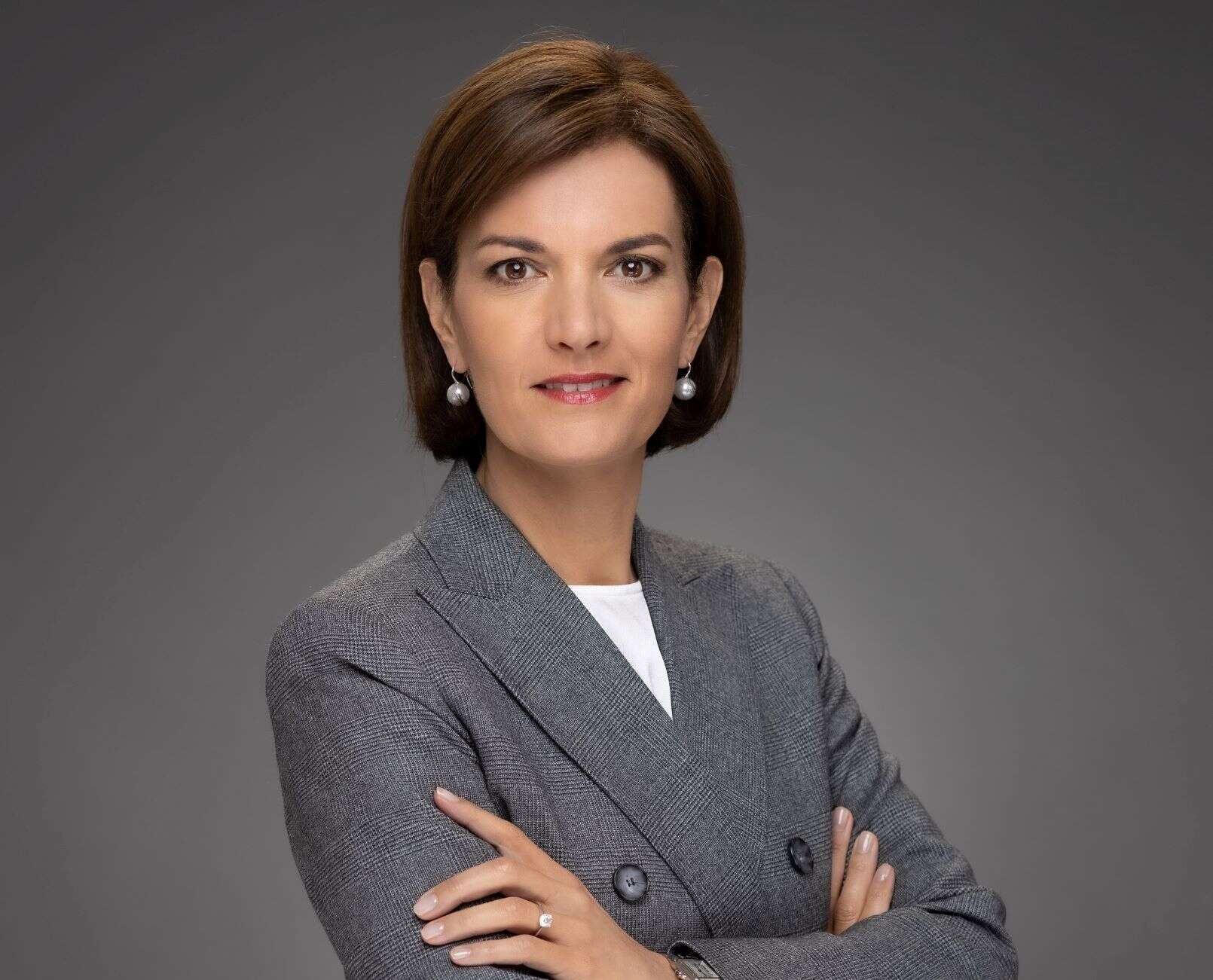

“We wanted to centralise green bonds on one platform,” LuxSE chief executive Julie Becker tells Capital Monitor.

LuxSE wasn’t the first to set up a green bond bourse – that honour goes to Oslo – but it is the biggest player, now listing 50% of the world’s GSS bonds. As of mid-June, it listed 1,304 such instruments: 754 green bonds, 485 sustainability bonds and 65 sustainability-linked bonds, with Euronext its closest rival (see chart). This is up from 1,234 totalling €640bn in 2021 and 830 totalling €388bn in 2020. It only discloses the value figures annually.

While the growth is impressive, there are issues around definition and regulation in the green bond market that need resolving – particularly given widespread concerns over how the proceeds of green debt are used or whether key performance indicators are sufficiently ambitious or robust.

After all, bourses work to support Esma in its key priorities, which Ross lists as: to promote transparency and tackle greenwashing; to build regulatory capacity at both EU and national level; and to monitor, assess and analyse ESG markets and risks.

Debate over green bond standard

Becker calls the European Green Bond Standard (GBS) – a voluntary initiative to help scale up and raise the environmental ambitions of the green bond market – the market “gold standard”.

Yet there is debate over whether it should be mandatory. In other words,for a bond to be classified as green you would have to apply the definitions as laid out in the GBS.

Speaking at the Icma conference, Alexandra Jour-Schroeder, deputy director general of the European Commission, said: “This will remain voluntary… there is no obligation in it.”

Becker is also keen to retain the status quo, warning that mandating the standard would threaten Europe’s leadership in sustainable finance – and, by implication, LuxSE’s commanding market position. Many issuers could not afford the cost of impact assessment reports and double verification by external bodies registered and supervised by Esma, she says.

And yet the expectation in some quarters is that mandatory green bond standards are likely eventually.

In a November 2021 opinion, the European Central Bank said “an immediate shift” to a strictly mandatory standard might lead to divestment from non-taxonomy-aligned green bonds and a sudden drop in [EU-]based green bond issuance”, but added that it should become mandatory for new issuances “within a reasonable time period”.

And Paul Tang, a member of the European Parliament responsible for drafting the proposal text for the GBS, agrees. “It’s the same problem as with the SFDR [Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation] – green financial products should be transparent, and if you say you are green you should [have to] prove it,” he says.

Data: missing links in bond reporting metrics

Where Becker would like to see more regulation is around data, “to bring legal certainty”. The exchange’s LGX DataHub has collected 150 data points for its listed bonds since September 2020, she says, but there is no harmonised framework of reporting metrics for green bonds.

“At the beginning, we lacked data – then we were swimming in data,” she says. The problem is that all the data comes from different sources that are not formatted or structured in the same way, rendering them not comparable. “What we need the most are convergence and collaboration,” Becker adds, but a lot of work needs to be done by both different standard setters and countries.

The European Financial Reporting Advisory Group (Efrag) and the International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB) on sustainability reporting standards have made progress, she adds, but it is “regrettable” that they employ different methodologies.

Similarly, while China and the European Union are working on a common ground taxonomy for global green finance standards, Becker points out that the US is missing from the initiative.

Wiener Börse’s green bond ambitions

While LuxSE leads the green bond market, other European stock exchanges have not sat idle in their efforts in this space.

Take the Vienna Stock Exchange (Wiener Börse), which listed its first green bond in 2014, a €500m ten-year 1.5% notes from Austria’s largest electricity provider Verbund. Having launched an ESG platform in 2018, in late May this year the exchange relaunched the platform as the Vienna ESG Segment, with requirements for disclosures and second-party opinions. Wiener Börse did so because there has been a huge increase in GSS debt in the past few years, says Silvia Stenitzer, green and social bonds expert at the exchange.

It has been making a virtue of cost. LuxSE charges an approval fee of €2,750 to list a bond, a listing fee of €1,500, and an annual maintenance fee of €500 to €800 per bond, depending on its size. Wiener Börse charges a listing cost of either €1,700 or €2,700 – the former if it is financial or public sector organisations, and the latter if it is corporates – and then an annual fee of €200 to €300.

Wiener Börse’s ambitions have been given a bump by the government. At the end of May, Austria sold a €4bn 1.85% deal maturing in 2049. It is listed on the exchange and is the first of a planned series of green issues.

Speaking at the Icma conference, Magnus Brunner, Austria’s federal minister of finance, said the rationale was to finance the expansion of public transportation and renewable energy. “We are planning to establish the republic as a frequent green issuer, and we have sufficient green assets to do so,” he added.

Wiener Börse is growing fast, with the number of bonds listed – both green and conventional – having surged to 7,083 last year from 3,166 in 2020 and 726 the year before. There has been similar growth in the green debt market, with 68 issues listed now, up from six in 2018.

Greater scrutiny of this burgeoning segment by both the participants in and supervisors of this market is inevitable. It is down to both sides to maintain appropriate standards.