- Brazil is the largest beef exporter in the world and accounts for 80% of deforestation in the country.

- The three largest beef trader groups in Brazil have received $1.1bn in credit in 2022 alone, according to Forests & Finance.

- The biggest lender, Bradesco, has practically no policy concerning the halting of deforestation.

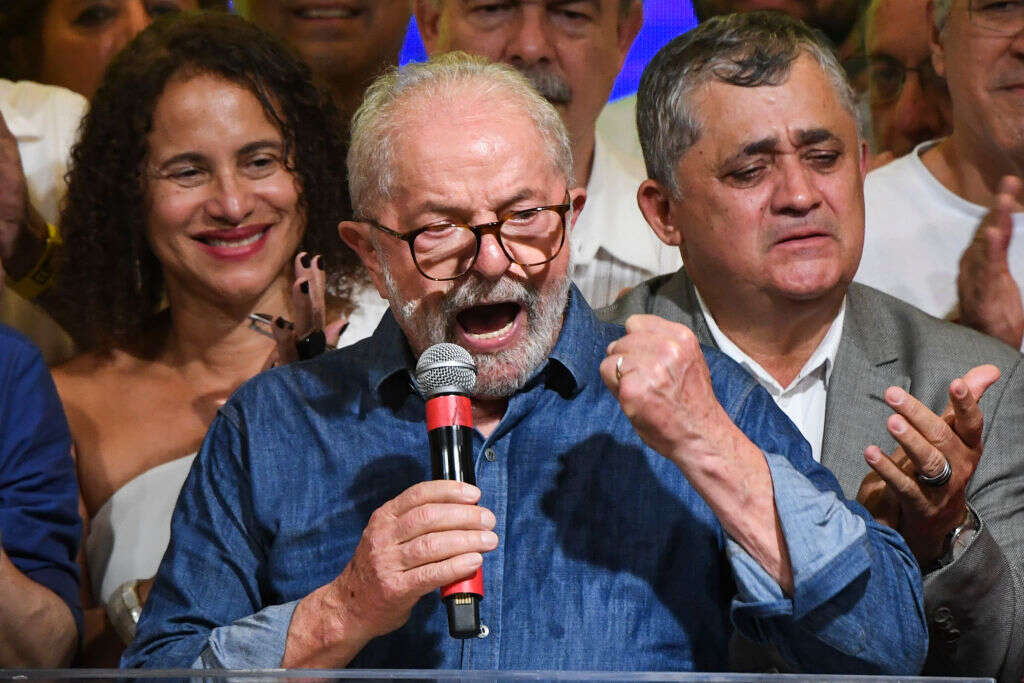

Just a few hours after narrowly winning the election, Brazil’s president-elect, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, committed himself to halting the continued destruction of the Amazon rainforest and to reinstating the country’s status as a serious international player on climate. He is attending Cop27.

Assuming a smooth transition, Lula will become president in January, but he has much to do to restore faith in the word of Brazilian politicians. The incumbent, Jair Bolsonaro, also pledged last year to halt deforestation. This proved devastatingly hollow; Amazon destruction hit a 13-year record in 2021 while budgets for environmental enforcement were slashed, severely hampering efforts to curb illegal logging and other environmental abuses.

Much will hinge on the political team Lula builds around him. Although no official announcements have yet been made, there is plenty of talk that seasoned politician, ally and environmentalist Marina Silva will be placed in a prominent position, presumably as the minister for the environment.

The individual – or individuals, as it may turn out – selected to run the Ministry of Economics will prove the most critical in supporting Lula’s environmental aspirations. In charge of implementing the country’s economic, fiscal and financial strategy, they will hold sway over the activities of the country’s financial services and the flow of foreign capital (via the central bank). The current minister, Paulo Guedes, is no great friend to the Amazon, it seems.

Banking on beef

Take the cattle industry, for example. Brazil is the largest beef exporter in the world; the market is also a key driver of deforestation in the country, contributing to the eradication of 37 million hectares of the Amazon since 1985, accounting for 80% of all deforestation.

It is also dependent on finance. The sector has attracted approximately $67bn in credit since 2016. The vast majority (89%) is via government-subsidised rural credit which supports the sector’s vast supply chain.

According to Forest & Finance, the three largest beef trader groups – JBS, Marfrig and Minerva – received 90% of all private credit, with JBS receiving $1.1bn in investment in 2022 alone.

Two of the largest suppliers of capital to JBS over the past five years are BNDES ($566bn) and BTG Pactual ($844bn) – the latter, incidentally, was founded by the current minister for the economy Paulo Guedes.

Despite all three making multiple pledges to reach zero deforestation over the coming decades, very little has happened so far to bring those commitments to life.

JBS, for example, has publicly committed to eliminating all cases of illegal Amazon deforestation from its supply chain by 2025 with a wider ambition to achieve zero deforestation across its global supply chain by 2035. Only last week, the company’s head of sustainability, Sam Churchill, admitted the significant difficulties it faces in gaining visibility within its supply chains.

“The biggest challenge for use with the deforestation target is in Brazil where the supply chains are incredibly opaque and it is really hard to track the cattle back to the point of origin,” Churchill said at the TropAg conference in Australia.

See no evil

The healthy flows of capital to companies such as JBS point to a financial sector with very little appetite for introducing or enhancing policies around deforestation, reduced peat degradation or slash-and-burn agriculture. According to data compiled by Forests & Finance, restriction on lending or investing in companies directly linked to such activities is extremely limited, with banks and investors showing scant evidence of curbing investment.

In a report published in October, Forests & Finance writes: “Our assessment of JBS, Marfrig and Minerva’s largest creditors and investors demonstrated limited ability to adequately mitigate these risks and prevent the financing of large-scale deforestation, forest degradation and human rights violations.”

Banks such as HSBC, which play an important role in supplying capital to Brazil’s beef sector, are one of the very few lenders with firm financing restrictions, says Forest & Finance; the major domestic banks, such as Banco Bradesco, far less so.

Forests & Finance also flagged Bank of America, BTG Pactual, Itaú Unibanco, BlackRock, BNDES and Manulife Financial for making some efforts to bolster policies constraining deforestation, slave labour and land conflicts in 2022, issues that have flared since Bolsonaro’s time in office.

Central to the problem?

And while attention from NGOs typically points towards the private sector, foreign capital from the world’s largest central banks has also found its way to companies with strong links to illegal deforestation.

In an attempt to inject liquidity into markets deeply affected by the pandemic, the US Federal Reserve, the European Central Bank and the Bank of England have pumped north of $160m into corporate bonds belonging to Archer-Daniels-Midland Company, Bunge, and Cargill, according to data compiled by Global Witness and published in September.

All three deny ties to deforestation of climate critical forests and, in defence of the central banks in question, injecting liquidity into companies that have a huge influence on the flow of agricultural produce across the globe during a pandemic may have averted more immediate humanitarian crises.

In the case of Brazil’s own central bank, it recently joined the Network for Greening the Financial System, a collective of central banks looking to share best practice and, in its own words, to “help meet the goals of the Paris agreement and to enhance the role of the financial system to manage risks and to mobilise capital for green and low-carbon investments”.

And there are more positive signals. As of July this year, all banks operating in Brazil are required to conduct climate-related stress tests and that climate is incorporated in credit risk management. Importantly, the central bank acknowledges the negative influence deforestation has on the climate.

How quickly this new reporting regime will translate into more restrictive lending practices remains to be seen. If Lula is truly serious about halting the destruction of the Amazon, then he must ensure the right people are overseeing the activities of the banking sector. More stringent requirements on transparency of supply chains must be a priority.

As challenging as it is, the consequences of failing to do so are far more devastating for Brazil and the rest of the world.