-

- The carbon-intensive nature of current stimulus packages are sparking fears of a repeat of the 2008 crisis when CO2 emissions spiked.

- China and India are the only countries in the top seven largest to have committed billions to supporting the coal industry during the pandemic…

- … But they have also committed more than half of their spending to clean energy, with China leading the pack.

In the second half of 2020, coal demand worldwide surpassed pre-Covid-19 levels, reversing the reductions in coal consumption observed during the first half of the year. China and India faced accusations of preventing a global green recovery from taking off, thanks to decisions to prop up their coal industries as a part of Covid-19 stimulus plans.

However, an analysis of data tracking the policy commitments for different energy types in both countries, alongside data showing their historic consumption across different energy types, reveals a more complex narrative – one where India and China are both the world’s worst polluters, while at the same time leading the global charge to a clean energy transition.

In the latest update from the Greenness of Stimulus Index (GSI), which assesses the sustainability of total Covid-19 stimulus efforts in all sectors, the world’s two largest producers of coal are considered distinctly lacking in their green recoveries. China’s performance is deemed “critically insufficient to achieve environmental targets”, whereas India’s is “highly insufficient to achieve environmental targets”.

Analysis by Vivid Economics, a strategic economics consultancy, examines the total economic stimulus packages of the world’s leading economies, which by February 2021 add up to $14.9trn, and finds that $4.6trn has been channelled to sectors that have a lasting impact on carbon emissions and nature, while less than $1.8trn is directed at ‘green’ policies.

Backing fossil in a crisis

As of 14 April 2021, most of the energy funding commitments made by G20 governments were for fossil fuels, which received a minimum estimated total of $277.9bn, or 41% of funding commitments, compared with at least $240.9bn, or 37%, to clean energy.

An example of such a commitment, which each span various time frames, is an announcement in March 2021 by Coal India for the approved investment of $6.4bn on mining projects, including eight new projects as well as expansion plans for 24 existing mines.

Honing in on the countries’ individual commitments to ‘unconditional fossil fuels’ – those that lack any conditions aimed at reducing emissions – China and India stand out as being the only countries whose governments have committed billions of dollars to the coal industry, which includes funding for new coal mining projects or coal-fired power plants.

Yet using data from the Energy Policy Tracker, which compiles the spending commitments of G20 countries specifically for different energy types (power, buildings, mobility, and other energy-intensive sectors), it’s clear China and India are simultaneously investing in carbon-intensive policies while committing huge amounts of money to green energy.

Adding in the green

China and India are in fact among the only countries to have committed more spending to clean energy than to fossil fuels, supporting the seemingly incongruous notion that while these two counties are the world’s largest emitters, they are also world leaders in developing renewable energies in terms of their public money commitments to clean energy.

To place this into context, Energy Policy Tracker’s estimation of policy commitments only accounts for around 3–5% of the total stimulus recovery commitments, as it only includes values that are available from official sources. Some policies included were drafted prior to the crisis and introduced after 1 January 2020, and so may not appear to be linked directly to the pandemic.

The tracker categorises each energy-related policy commitment according to whether it primarily supports green energy or fossil fuels and assesses whether or not those countries have imposed conditions on those commitments. Monetary and fiscal policies are also captured.

As emerging economies, both India and China have both made remarkable transitions towards clean energy over the past few years. In 2019, China consumed more renewable energy than any other country in the world, while India was the fifth-highest consumer, rising to the fourth highest in 2020.

In India, an enormous effort has gone into the transition to low-carbon LED lamps, the market share of which grew from 0.3% to 46% in five years. India is also expected to see an explosive growth in solar power over the next two decades, which, according to International Energy Agency (IEA) predictions, is expected to match its coal share in that time.

Alongside the US, China is the driving force behind global net installed renewable energy capacity, and its wind and solar photovoltaic (PV) additions are set to jump by 30% by 2025. As an IEA analysis notes, renewables have been extremely resilient to the Covid-19 crisis, and China’s recently announced net-zero emissions target of 2060 is expected to accelerate the deployment of renewables.

An unusual energy transition

Both China and India occupy a unique global position as emerging economies that have gone straight from a huge dependence on coal to large investments in renewable energies.

China and India were among the world’s largest suppliers of both coal and renewables, according to 2019 data sourced from the energy company BP. This highlights their unusual transition to clean energy compared with most countries, for which the general pattern is to gradually wean first off coal and move onto alternative, less carbon-intensive energies like natural gas, before investing in renewables.

So despite spending more overall on clean energy than fossil fuels as part of their Covid-19 recovery packages, China and India’s overall Covid-19 stimulus policies announced by February 2021 are assessed by the GSI as having a net negative environmental impact, since scores are scaled to account for the intensity of the environmental impact of their policies.

Investments in green energy, in environmental terms, are outweighed by investments in coal projects, which are dubbed ‘intense negative’ policies and therefore earn more GSI points. Yet while maintaining net negative environmental scores, both India and China are noted by the GSI as having ‘considerably’ improved their scores, thanks to recent green policies that include investments in clean energy, and in China’s case, major forest restoration plans.

They also include China’s announcement in December last year that it has increased the ambition of its 2030 climate targets by vowing to lower emissions per unit of GDP by over 65% from its 2005 levels, and India’s five new green stimulus policies announced since the start of 2021, which include renewable energy and energy-efficiency schemes.

Compared with more developed economies, the embeddedness of coal in China and India’s economies is significant and raises the spectre of how easy it will be for these economic giants to wean themselves off.

In 2008, at the time of the global financial crash, India and China’s coal rents spiked wildly compared with that of other countries, illustrating their dependence on the sector, on which a large proportion of their populations’ jobs are contingent. Post 2008, global CO2 emissions grew 5.9% in 2010, and the carbon-intensive nature of current stimulus packages are sparking fears that we will see a repeat situation in the coming years.

The politics of coal

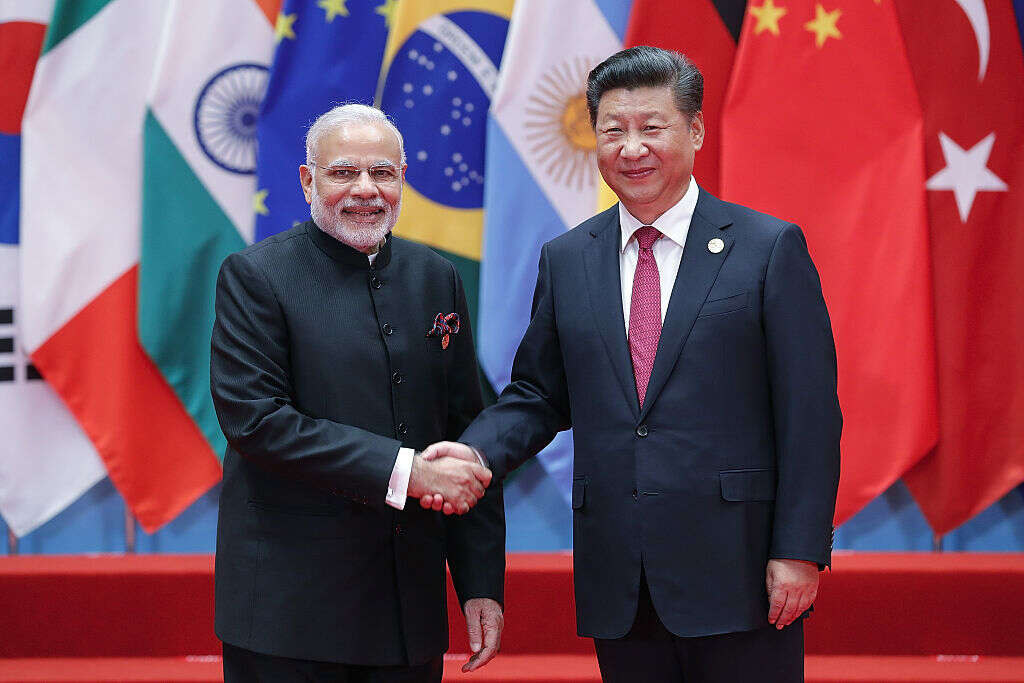

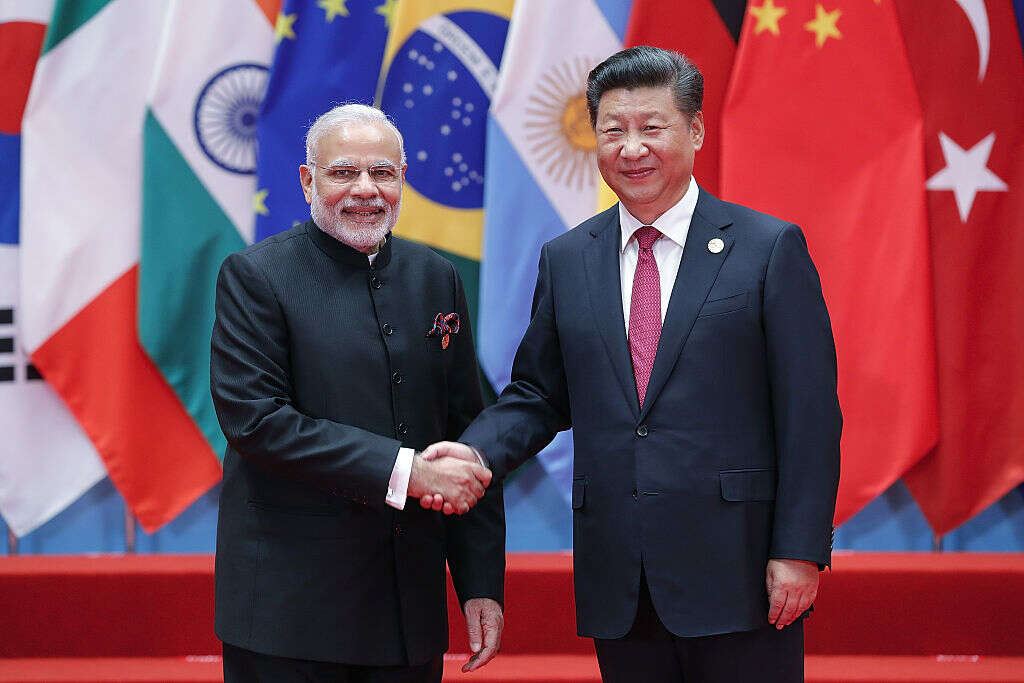

Leaning on coal in a time of crisis presents both risks and opportunities – some longer-term than others. Last year in India, Prime Minister Narendra Modi claimed – alongside announcing the launch of an auction process for 41 coal mines for commercial mining – that “allowing the private sector in commercial coal mining is unlocking the resources of a nation with the world’s fourth-largest reserves”.

While making use of ample reserves is one way for a county to achieve self-sufficiency in terms of meeting energy needs, as the world decarbonises, plans to expand the use of coal-based power plants risk leaving emerging economies like India with stranded assets.

Both India and China are currently at a juncture, where their huge expansions of green energy alongside their continued funding of the fossil fuel industry provides them with simultaneously some of the greatest opportunities and the largest challenges when it comes to making a green transition post-pandemic. Whether their large injections into green spending will start to have a net impact on their overall emissions is yet to be seen.