- The world’s five largest oil and gas companies reported earnings of $158.8bn last year.

- Outrage continues at UAE hosting the Cop28 summit this year with Sultan Ahmed al-Jaber, chief executive of state oil giant Abu Dhabi National Oil Company (Adnoc) named as president of the climate conference.

- This year’s summit includes the first global stocktake review of climate change since the Paris Agreement in 2015.

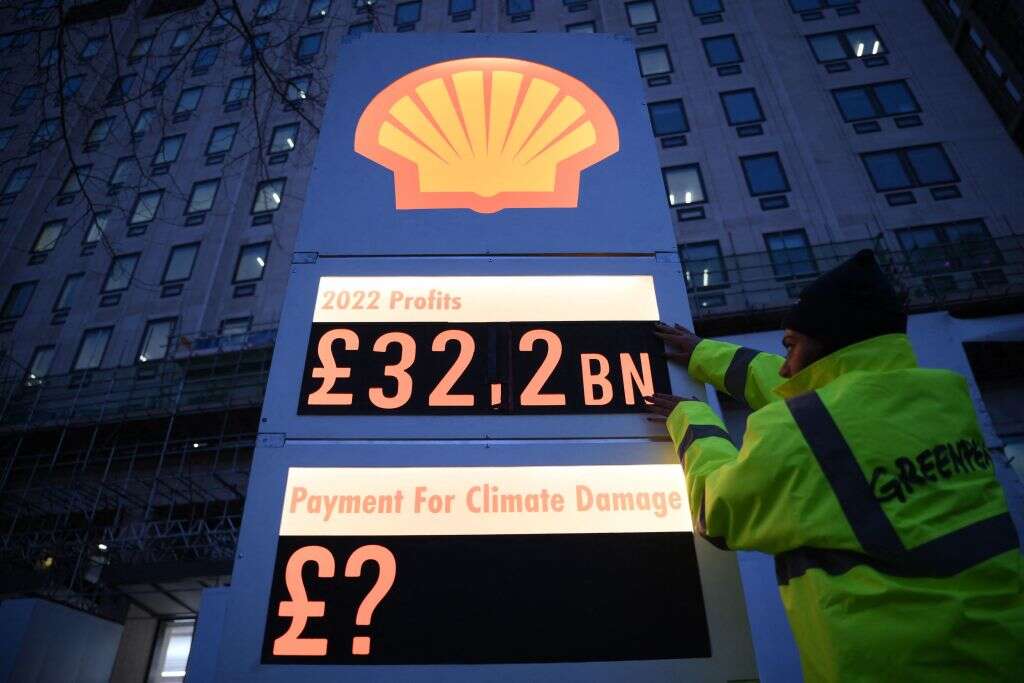

The message about climate change does not appear to be getting through. The fourth quarter profits of the major oil companies were breathtakingly large [see chart].

As Simon Evans, senior policy director of London-based climate change policy specialists Carbon Brief pointed out, the profits of the world’s five largest oil and gas companies were the equivalent of $220 for each one of the 719 million people still living in extreme poverty today.

Profit in and of itself is not a bad thing – it is what you do with it that is important. And this is where the problems begin.

Over the past couple of weeks, France’s TotalEnergies has confirmed that 70% of its new investments are going to be in new oil and gas fields; as Capital Monitor discussed last week, BP has scaled back on its commitments to cut the energy company’s Scope 1 and Scope 2 emissions by 2030; and Shell has found itself in the law courts again over the snail’s pace of its transition.

Last week, a group of European institutional investors, including UK pension funds Nest and London CIV, Swedish national pension fund AP3, French asset manager Sanso IS, Degroof Petercam Asset Management (DPAM) in Belgium, as well as Danske Bank Asset Management and pension funds Danica Pension and AP Pension in Denmark, filed a lawsuit alleging climate mismanagement.

Public feeling is high. “Fossil fuel giants like Shell are climate criminals – and the directors and chief executives who run them must be held personally accountable,” tweeted Caroline Lucas, a British member of parliament.

In a speech to the UN general assembly last week, UN secretary-general António Guterres bluntly said to the oil majors: “Your core product is our core problem”. A great soundbite, but the problem remains how to engage with them.

A conflict of interest

There was discontent about Cop28, this year’s United Nations climate summit, even before the delegates packed their bags at Sharm El Sheikh in November last year.

The howls of outrage about being hosted in November this year by the petrostate United Arab Emirates become louder when Sultan Ahmed al-Jaber was named president of the climate conference. As chief executive of state oil giant Abu Dhabi National Oil Company (Adnoc), this makes him the first head of a state oil company to head the global summit.

The backlash was inevitable. “This might be controversial, but I think it’s okay to uninvite big oil to global climate negotiations after they’ve repeatedly shown that they have no intention whatsoever of winding down production, funding renewables, and staving off human extinction,” suggested Tzeporah Berman, international programme director at Stand.earth and the chair of the Fossil Fuel Non-Proliferation Treaty Initiative, last week.

At the Davos summit in Switzerland this year, former US vice president and climate leader Al Gore criticised the choice of al-Jaber and said that the nomination had “the appearance of a conflict of interest”.

In January, the world’s largest environmental and climate action groups including 350.org, Friends of the Earth International and Greenpeace wrote a letter to the UN objecting to the appointment.

“There is no place for the fossil fuel industry in the global climate negotiations,” it concludes.

Even the UN gave the appearance of distancing itself from the decision. In mid-January, UN spokesman Stephane Dujarric made it clear that the Cop president is chosen by the host country with no involvement of the UN secretary-general or the secretariat of the UN framework convention on climate change.

Pragmatism and constructive dialogue

It is true that Adnoc’s climate ambitions are so laughably small that they make those of rival Saudi Arabian Oil Company (Aramco) look fully engaged.

The company has committed to reducing the intensity of only its operational greenhouse gas emissions by 25% by 2030 and says that it is heading towards net-zero emissions by 2050. It doesn’t even publish a sustainability report.

But given that both banks and investors have been slow to halt investment in oil and gas companies, perhaps having them in the room is a more fruitful way to engage with them. That is the argument of US special climate envoy John Kerry who has emphasised engagement for the past few months.

In an interview with Reuters before Christmas, he underscored the importance of having “an oil and gas producing nation step up and say we understand the challenge of the climate crisis”.

Al-Jaber himself has called for “pragmatism and constructive dialogue”. The spectre of greenwashing has continued to loom large over the Cop summits since last year’s meeting in Egypt and US congressman Jared Huffman summed up the concerns of many when he warned that Cop28 could be “the lost climate summit”.

The presumption has been that Cop28 has been hijacked by the oil industry and to think the worst of UAE. But given that this year’s summit is the first global stocktake review of climate change since the Paris Agreement in 2015, pragmatism and constructive dialogue is the only way to proceed.

It is easy to mock al-Jaber’s aims “to build consensus and coalitions to achieve a practical, pragmatic and just energy transition”. But no more plausible solutions have been put forward.

The stocktake is going to be a hard message for many to absorb. By the time the summit closes on 12 December, countries, banks and investors will have nowhere to hide.