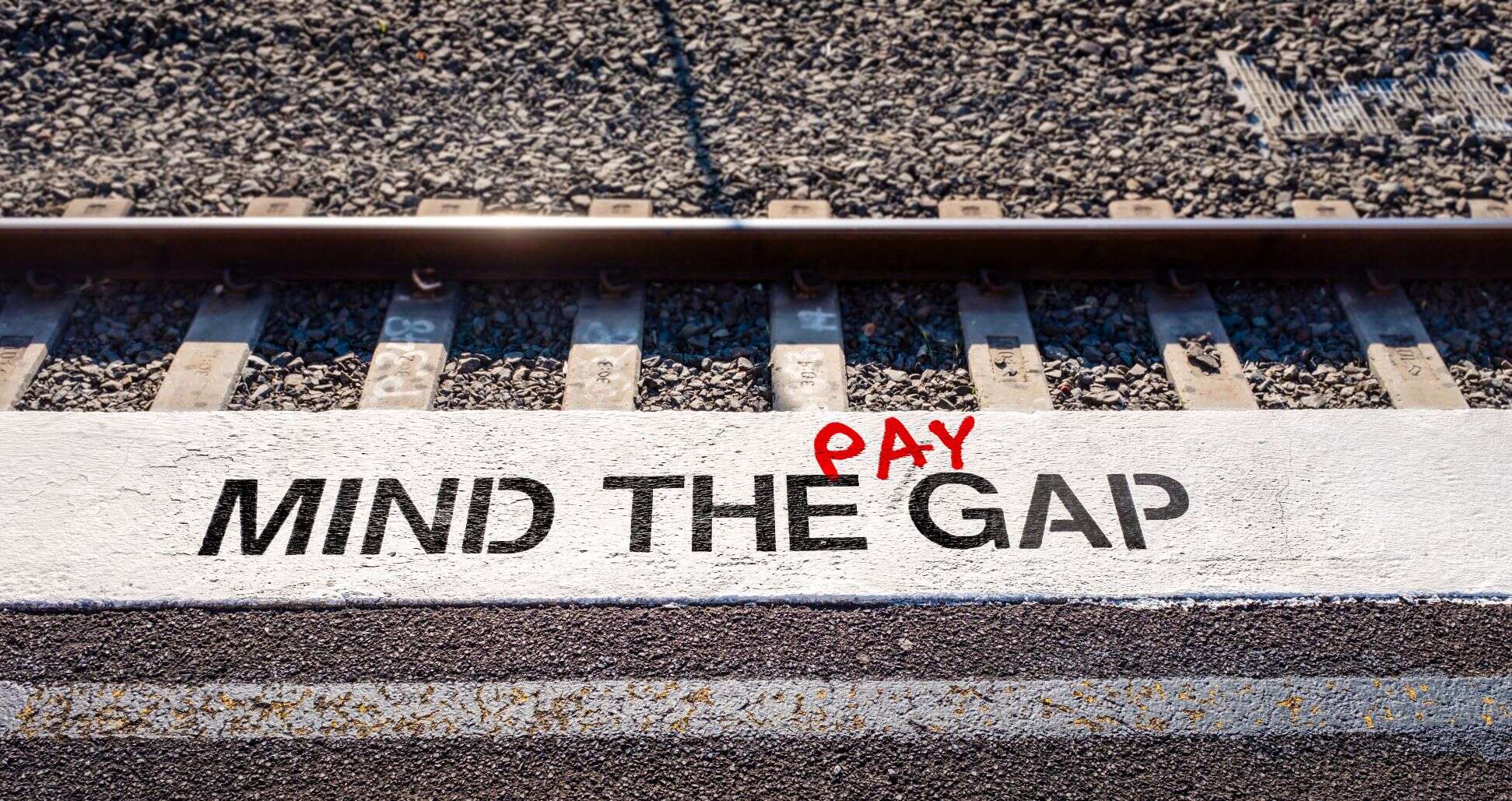

- UK’s gender pay gap has narrowed faster since mandatory reporting started in 2017, although the data gathering and analysis process has flaws.

- Nonetheless, the requirement has forced firms to address employee concerns related to remuneration, diversity and inclusion.

- Despite narrowing in the past five years, the finance and insurance sector is reporting a median gap of 33.2%.

The requirement for UK companies to report on their gender pay gaps is helping, gradually, to narrow the differential between men’s and women’s remuneration. Importantly, it has also highlighted issues related to diversity and inclusion and is forcing employers to address difficult questions around workplace inequality.

The overall median gap has shifted 22 percentage points since 1998, according to the Office for National Statistics, although mandatory reporting of such data is a recent phenomenon.

Since April 2017, British companies with 250 or more employees have been required to publish their gender pay gap for the year prior. Data from 2019, when most firms last reported, show that eight out of ten paid women less than men.

The gap has been narrowing steadily since 2000, when it was 26.7%, but that trend accelerated in 2019, the first year to fully reflect the impact of the rules (see graph below). And in 2020 the median gender pay gap fell year-on-year to 15.5% from 17.4%, although most companies have not yet reported (see graph below).

This year, the reporting deadline has been extended until October because of the pandemic, though companies are encouraged to report earlier. Hence this year’s figures are likely to be telling. Female employment has been hit especially hard during Covid-19, largely because women were more likely to work part-time and to be furloughed. As a result, companies that made the most use of the government’s job retention scheme are likely to see their gender pay gap widen this year.

More action required

The increased transparency in this area is clearly welcome, but the data itself is little use unless it is being acted upon.

“It’s not so much the exact size of the gap that’s important… it’s about the action the company is taking to address it,” says Charlotte Woodworth, gender equality campaigns director at London-based non-profit organisation Business in the Community.

“We’re hearing from an increasing number of businesses that they’re discussing diversity and inclusion at corporate away days, which is a big development,” she adds.

Yet the most effective action includes companies making changes on issues such as maternity support, parental leave and job sharing. Firms with the smallest or negative gender pay gaps, such as UK consumer products conglomerate Unilever, typically have well-established policies in such areas.

Oil major Shell, for example, saw its median gap narrow to 18% last year from 23.4% in 2017. That’s a meaningful shift for a big company in a traditionally male-dominated sector. It represents considerable work behind the scenes including introducing better maternity pay, flexible working options, quarterly diversity monitoring, management programmes for women, and other initiatives to encourage more young women to study in areas such as science, technology, engineering and mathematics.

It’s important that organisations know there’s going to be a degree of ranking. We want people to feel their feet on the fire. Charlotte Woodworth, Business in the Community

The public nature of the reporting has prompted unprecedented employee engagement, which can then work its way into day-to-day decision-making, Woodworth says. “It’s important that organisations know there’s going to be a degree of ranking. We want people to feel their feet on the fire.”

Indeed, the UK reporting rules have helped to make pay and gender inequality a boardroom issue and driven significant improvements in governance systems.

Between 2012 and 2019, average wages for women at companies required to report their pay gap increased by 1.6% relative to men, according to analysis published in March by the London School of Economics. The change was not down to putting more women in highly paid positions – often seen as something of a short cut – but to changes in individual workers’ wages, the research said.

This suggests that what gets measured really does get managed, which is a valuable lesson for the broader issue of sustainability reporting, says Tim Mohin, chief sustainability officer at carbon footprint measurement firm Persefoni, and former chief executive of the Global Reporting Initiative.

Pay gap brand concerns

Charles Cotton, senior performance and reward adviser at the UK’s Chartered Institute of Personnel & Development (CIPD), supports this view.

“Organisations are definitely concerned about the impact a large pay gap could have on their brand,” he says. "They can… view it as a risk, or as an opportunity, in that investors may be more likely to put their money into the company, and potential employees are more likely to want to work there [if it has reputation for fair pay].”

The BBC provides a high-profile example. As a public entity, in 2017 the broadcasting corporation was required to publish the salaries of its highest-earning presenters. The data revealed a shocking imbalance between men and women.

It emerged that all seven of the top earners were male, and that there were huge gender discrepancies: Chris Evans, the highest-paid man, took home £2.25m, while the highest-paid woman, Claudia Winkleman, made £450,000.

After significant changes last year, including several of the male presenters taking a pay cut, the gap had fallen to 6.2% from 6.7% in 2019.

Ultimately, of course, change tends to happen faster if it is mandated. And that is seen as a drawback of the UK rules: they recommend companies comment on any pay gap, but don’t require them to do anything about the situation.

Accordingly, groups such as Business in the Community have pushed for businesses to be forced to publish an action plan detailing remedies alongside the data.

Tom Gosling, executive fellow at the London Business School (LBS) Department of Finance, says: “In the UK, we have a habit of using disclosure rules to nudge broader change. That can be helpful, but sometimes you need bigger changes to laws surrounding it, including [on] maternity support, parental leave and job sharing.

“Nudges can only get you so far,” he adds. “The reality is that it’s representation issues that drive the gap.”

Not all as it seems

There are, though, caveats around the findings. There are several potential reasons for a pay gap, and some are not simply down to the fact that a particular company pays women less than men for the same type of work.

Organisations are definitely concerned about the impact a large pay gap could have on their brand Charles Cotton, Chartered Institute of Personnel & Development

Most often, it’s because there are more men in senior positions than women: a separate but important issue. This is particularly acute in financial and professional services, where the median male-female pay gap at individual companies can be as high as 36%.

It’s no coincidence that working practices are particularly inflexible at many such firms, which typically use billable hour structures and expect employees to be available to clients around the clock. While these companies hire similar numbers of male and female graduates, management teams and partnerships are overwhelmingly male.

Many of these firms have made progress, but with employees typically serving long tenures, it can only shift so fast. Some sectors, such as financial services, have historically huge gender pay gaps that will take many years to close, notes Woodworth (see table below).

There can also be more than meets the eye to a widening gap, Gosling says. For instance, a company that has made a conscious effort to diversify its talent pipeline by hiring more women for entry-level positions may see its pay gap initially widen.

Life insurer Prudential is one financial services company that saw its gap widen in 2020. However, as its report notes, this is largely down to a demerger that saw most of its senior female staff depart to M&G. But since mandatory reporting began, it has introduced a new talent pipeline initiative and enhanced its maternity support.

After all is said and done, even ardent campaigners for reducing the gender pay gap recognise that completely eliminating it is not realistic, especially in certain industries. Indeed, trying to do so can often create other problems.

“If companies [in certain industries] try to get to zero, you can easily see how they could end up doing some jiggery-pokery, like thinking about letting go of highly paid men,” says CIPD’s Cotton. “It’s more important to look for an overall balance.”

The male-female pay differential is thus set to remain a hot-button issue, as it seems unlikely to ever disappear. At least rising transparency on the issue is forcing companies to maintain a fair approach and more open communication with their employees.