- Britain’s sustainability policy has a strong focus on financial disclosure, but less so on concrete, practical action.

- There should be more focus on areas such as transport and homes, which account for at least 40% of domestic emissions.

- The government can afford to implement more impactful policies with the £16bn ($19.3bn) of green debt it raised last year – and a further £10bn on the way.

The UK appears to have based its sustainability policy on Tariq Fancy’s recommendations of what not to do.

BlackRock’s former head of sustainable investing argued – during his three-part essay last year slamming the model – that so-called sustainable finance was counterproductive as it distracted from impactful government policy.

That is more or less what is playing out in Britain.

From this financial year, all companies, banks and insurers with more than 500 employees – and all pension funds – in the country have to produce reports in line with recommendations from the Task Force for Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD).

These reports show how businesses are considering the risks that climate change poses to their business and will soon be expanded to include whatever recommendations are produced by the International Sustainability Standards Board.

Next will come taxonomy reporting, whereby companies will have to disclose how much of their operations align with the green taxonomy being drawn up by the Treasury.

Meanwhile the Bank of England is ahead of the curve on conducting – and publishing the results of – climate stress tests assessing how prepared banks and insurers are for climate change.

According to the government’s Greening Finance roadmap, such disclosures are necessary so that investors can decide whether companies are truly green and company-level data can be used to verify the sustainability claims of financial institutions.

It is not clear, however, whether any of this actually makes anything more sustainable. The idea that shareholder engagement can meaningfully impact corporate sustainability is yet to prove itself. And we’ve yet to see evidence that improved corporate sustainability makes equity and debt financing cheaper to the point where it provides strong financial incentives.

UK sustainability policy shortfalls

The cost-of-living crisis – the substantial fall in ‘real’ incomes that Britain and other countries have experienced since late 2021 – has exposed the shortfalls of the UK approach to sustainability policy. That is, its lack of concrete practical action that would reduce costs for households.

Even the US has acknowledged as much with its new Inflation Reduction Act, which will provide tax credits for home energy efficiency upgrades such as heat pumps and insulation – despite the recent fierce political anti-ESG backlash.

The UK could afford to take similar action. It raised £16bn ($19.3bn) from two green bonds last year: a 12-year issue in September and a 32-year in October. It opened these issuances up again in May and plans to sell a further £10bn of green debt this financial year.

At a conference hosted by the International Capital Market Association last month, Robert Stheeman, head of Britain’s Debt Management Office, said demand for UK green bonds was high and that they were to become a lasting feature of the national debt.

“We did not want this [green bond] to be a one off…we wanted to make it part of a programme,” he added.

The 12-year issue attracted the largest number of different investors ever to participate in a syndicated gilt offering for the UK, Stheeman said, including some buying gilts for the first time.

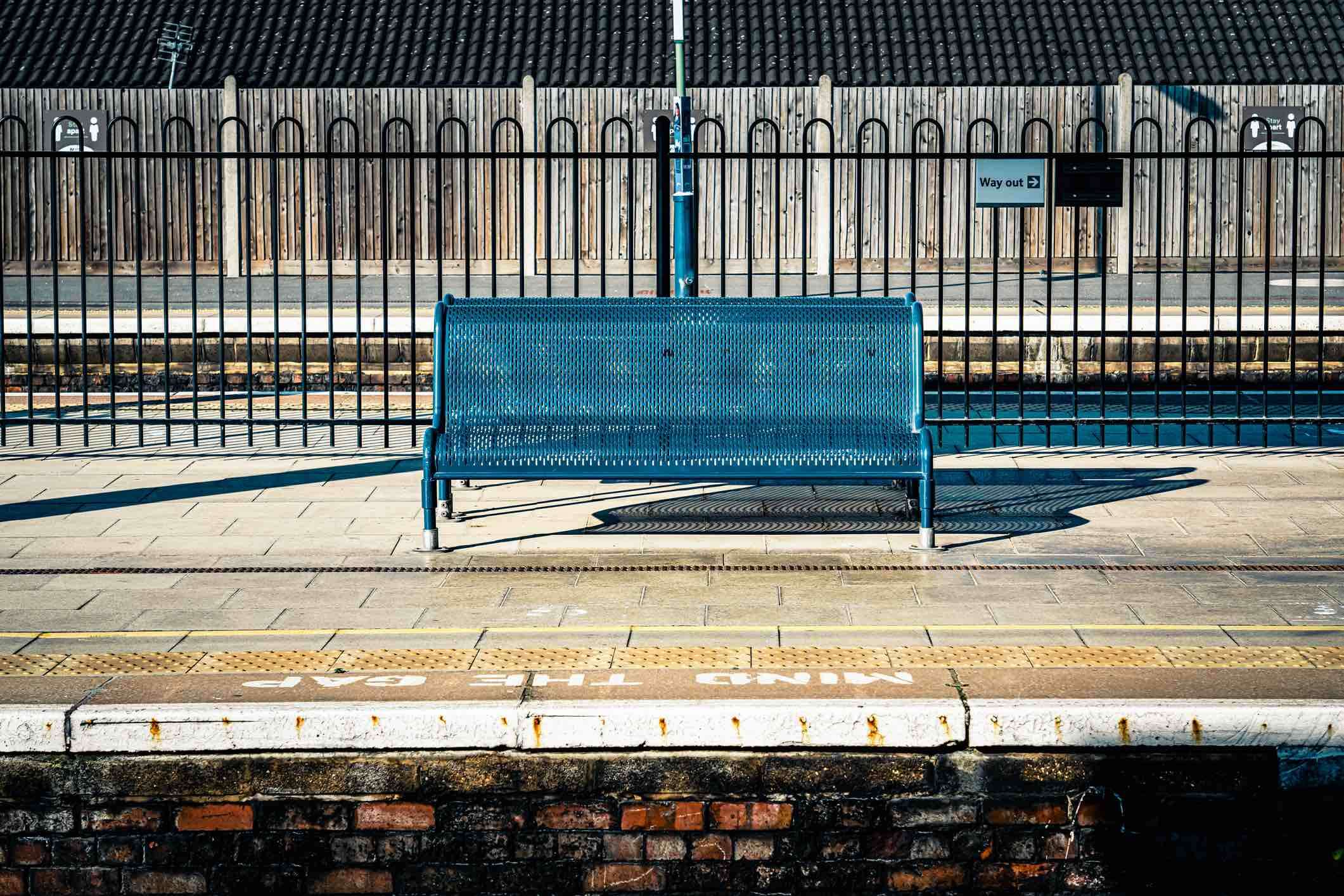

Other sovereign green bond issuers are tending to put their money into railways and making buildings more energy efficient, shows Capital Monitor analysis.

Most of France’s green bond proceeds have gone toward providing interest-free loans for energy efficiency home improvements. In Belgium, the vast majority has gone into rail subsidies and investment. Chile, one of the most prolific green bond issuers, has put 92% of its proceeds into rail. And Singapore just last week sold a sovereign green bond with the longest ever tenor – a 50-year issue that raised S$2.4bn ($1.74bn) for new rail lines.

Transport and property offer opportunities

The UK should consider following suit to ensure a very long-term, stable source of funding for green projects.

Transport is the country’s most polluting sector, accounting for 24% of greenhouse gas emissions, according to the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy. Within transport, 69% of emissions are generated by cars and vans and 18% by lorries. Property is another major polluter. Household combustion contributes 16% of emissions, mainly due to gas boilers.

If the government were to focus on these areas rather than putting so much emphasis on financial reporting, it could quickly reduce both emissions and the cost of living.

Instead, we have the Williams-Shapps plan, which will bring more of the UK’s fragmented rail network under the control of a new body called Great British Railways. It is targeting savings rather than looking to cut ticket prices, expand services or do other things that might attract passengers and help reduce car use.

Then there is the Energy Company Obligation (ECO) scheme, which seeks to provide those in fuel poverty with home improvements, with £4bn earmarked for helping 450,000 homes over the next four years. This is part of a total of around £8.2 billion in funding out to 2026 from the government for energy efficiency and low-carbon heat retrofits in fuel-poor homes.

But the UK Climate Change Committee’s 2022 report to parliament, published on 29 June, said: “Recent record increases in energy prices mean that this allocation is unlikely to be sufficient, as it was based on fuel poverty estimates which predate price rises.”

The ECO scheme is paid for by energy companies that recoup costs by charging customers more. The government should support a broader rollout of the scheme backed by public funding.

More green gilts needed

Sustainable finance can have an impact by helping green projects raise capital they need at a volume and cost they could not have achieved otherwise.

Instead of spending its time imposing sustainability disclosure requirements on the private sector, the UK government should aim to be a major source of green projects. After all, it has plenty of potential to ramp up green bond issuance, which accounts for only a tiny fraction of British national debt. And investor demand is there: the green gilt programme has been 12 times oversubscribed, according to HM Treasury.

Admittedly, the remaining two contenders to replace Boris Johnson as prime minister – particularly frontrunner Liz Truss – do not have promising climate policy records or plans. Let us hope the successful candidate recognises the need to improve on those.

Capital Monitor is hosting the Webinar series, Making Sense of Net Zero. Find out more information on NSMG.live.