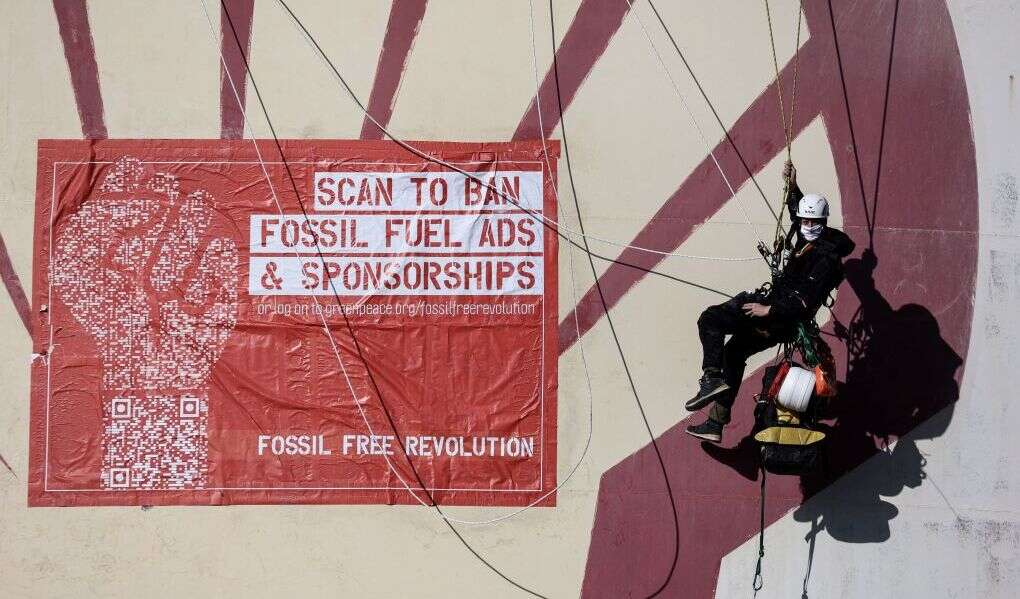

Calls are growing louder for a ban on fossil fuel advertising. (Photo by Kenzo Tribouillard/AFP via Getty Images)

- Fossil fuel company advertising and marketing is facing rising scrutiny, as consumers become more climate-aware and less tolerant of greenwashing.

- Lawmakers are starting to investigate how energy companies have influenced public thinking about the environment in what is a growing area of litigation.

- Advertising and public relations firms are also now under pressure to consider their clients’ level of emissions, not just their own.

In 2011, the UK advertising watchdog banned an advertisement from energy major ExxonMobil for overstating the potential of algae as a low-emissions biofuel and thereby misleading consumers.

The public may also have been interested in some other relevant context: since 2009, Exxon has so far spent a mere (cumulative) $300m of its $25bn annual budget on algae research. This number is dwarfed by the total it spends on new oil and gas exploration and environment-related lobbying: about $1.2bn and $6m a year, respectively. The company aims to be producing 10,000 barrels of algae-based fuel a day by 2025; its current daily oil and gas output is four million barrels.

However, as consumers become more environmentally conscious – and more aware of fossil fuels’ huge contribution to global warming – they are wising up to, and becoming less tolerant of, misleading marketing. This trend is not lost on investors in, or participants of, the energy sector.

“Five years ago, this [concern over energy sector advertising] was not a topic,” says Robert Brulle, visiting environment professor at the US’s Brown University. “The critical thinking has really evolved to make it much harder for energy companies to get away with it, so they have had to change their methods.”

Rising regulatory scrutiny of advertising

Complaints to advertising regulators and campaigns for outright bans on fossil fuel advertising are reportedly on the rise and increasingly making their way into the courts too. At least 20 judicial ‘climate washing’ cases have been filed in the US, Australia, France and the Netherlands since 2016, largely on the grounds of misleading or deceiving consumers, according to a report published this year by the Climate Social Science Network, an international network of scholars.

Greenwashing regulations aren’t going to be able to deal with adverts that don’t specifically address climate change because they’re not technically making claims that are untrue. Robert Brulle, Brown University

Moreover, a US House oversight committee in late October quizzed oil company CEOs on their role in spreading climate misinformation and subpoenaed documents disclosing their advertising and public relations (PR) budgets and how they were spent. The second hearing is scheduled for 8 February; the committee has requested the presence of executives from oil majors BP, Chevron, ExxonMobil and Shell.

Blatantly false claims, such as that jet fuel or natural gas are sustainable, might well prompt a call from the regulator. Of greater concern, Brulle argues, are energy company adverts that do not explicitly try to sell a product and do not allude to climate change or emissions at all, such as the latest iteration of Exxon’s algae campaign.

Shell, meanwhile, claims to be part of the “greatest push for renewable energy the world has ever seen” while spending $2bn per year on its low-carbon businesses as against its $17bn annual outlay on fossil fuel operations.

“Greenwashing regulations aren’t going to be able to deal with adverts that don’t specifically address climate change because they’re not technically making claims that are untrue,” says Brulle.

Figures on advertising spend are hard to come by but significant. In 2015 alone the five biggest US energy companies – ExxonMobil, BP, Chevron, Shell and ConocoPhillips – spent $101.4m, although the figure has been falling since 2012 (see chart below). Still, the same companies and their industry bodies spent $2m on targeted Facebook and Instagram ads during the run-up to the 2018 mid-term elections in the US, according to a 2019 analysis of some 25,000 oil and gas ads by UK think tank InfluenceMap.

Such figures dwarf the advertising outlay of environmental groups (see chart below). “We’ve ended up with a communications process in which one side is 20 times larger than the other,” says Brulle. “What does that do to the notion of rational public discourse?”

Fossil fuel executives – like their counterparts in other sectors – themselves know very well how powerful adverts can be. For example, Mobil in 1981 said in internal documents that it had moulded the “collective unconscious” of the American public on this topic, according to an article in The Harvard Gazette.

Advertising and PR feeling heat

While fossil fuel companies have long been in the firing line, the advertising and PR sector is now also feeling the heat. In January, around 450 scientists shared an open letter, organised by campaign group Clean Creatives, that they had sent to PR firms asking them to drop fossil fuel clients. Under particular scrutiny is Edelman, which has many lucrative contracts to represent big emitters.

Sustainability discussions in the advertising industry have largely focused on how to reduce emissions from agencies’ own operations, but the industry is starting to think about the content of its clients' adverts and their potential effect on the environment, says Ben Downing, global head of media ethics at Havas Media Group, which has in the past worked with BP, ExxonMobil and Total Energies. As in many industries, media agencies' Scope 1 emissions are dwarfed by those of their clients in high-carbon sectors.

Ben Downing of Havas Media Group says the advertising industry has largely focused on how to reduce the emissions from agencies’ own operations, but they are dwarfed by those of their clients. (Photo courtesy of Havas Media)

The London-based Advertising Association, which represents 30 media agencies in the UK, promotes its ‘ad net zero’ initiative launched in November 2020 on its website. It focuses on reducing the carbon impact of advertising companies’ operations, but does not address client work or the content of adverts. Its CEO, Stephen Woodford, says the content of advertisements will change “as the economy changes”.

He argues that the UK’s legal frameworks and non-governmenal organisation (NGO) community are robust enough to keep companies in check. “The potential reputational damage [of a misleading advert] is just not worth the risk for most firms," he says.

And yet misleading marketing material appears to be widespread. In January last year the European Commission assessed 500 websites advertising environmentally friendly products and services. It found that four in ten such sites used tactics that “could be considered misleading and therefore break consumer law”.

Several initiatives have sprung up to push for more ethical advertising. For instance, the UK-based Conscious Advertising Network launched in 2019 and has 150 members, including media agencies and advertisers. Its disinformation manifesto commits signatories to ensuring they are not backing fake news, clickbait and other intentionally misleading content.

Doing so is difficult without clearer definitions and standards for greenwashing, but lessons can be learnt from how regulators have addressed online disinformation about Covid-19, says the organisation’s co-chair, Harriet Kingaby.

“We know that advertising is an incredibly effective form of communication, and that greenwashing really does confuse people, which often makes them switch off,” she adds.

The bottom line

Investors are also an important part of the equation, given their financial heft. They will be acutely aware, firstly, that regulatory fines, court appearances and a consumer backlash for corporates can hit share prices hard; and secondly, of the increasing scrutiny of the carbon intensity of their own investment portfolios.

Accordingly, in recent years investors have been successful in persuading companies to leave trade associations, improve their climate disclosures and put their net-zero plans to a shareholder vote, based on environmentally related arguments.

Four big fund managers contacted by Capital Monitor declined to comment on the issue of corporate greenwashing in advertising and the potential backlash from investors against overstated claims.

Degas Wright, chief executive of Decatur Capital Management, was the only asset manager to provide a view, saying public perception of companies is important as perception relates to market sentiment, which drives stock price. Hence Decatur employs sentiment analysis – how a company is viewed based on external sources, including analyst reports, social media and news reports – as one of its investment metrics.

The sector is certainly concerned by the issue of corporate greenwashing, agreed UK-based Aviva Investors in an article published on its website in May last year.

As they should be, suggests the Climate Social Science Network. It argues that corporate net-zero pledges will fuel litigation, pointing to “the lack of clarity or certainty over whether these commitments will be achieved… because there is no clear methodology applied to the claims”.

Thousands of companies have now made a net-zero pledge of some kind. Given that they are keen to impress, such claims can be laced with hyperbole, making them ripe for potential future legal action.

Short sellers are reportedly targeting corporates with particularly ambitious sustainability plans. Some are even doing so with the explicit aim of driving down carbon emissions.

And last year the investor backlash against climate claims reached the courts. In a first-of-its-kind case, shareholders in Australian natural gas producer Santos filed a suit disputing the company’s net-zero pledge.

Shareholders do not like regulatory fines, and they are even more averse to litigation, which often leads to caseloads of subpoenaed documents, uncomfortable executive testimonies and unsavoury soundbites.

Oil companies and their PR firms are unlikely to be the only ones nervously watching the US House’s next session.