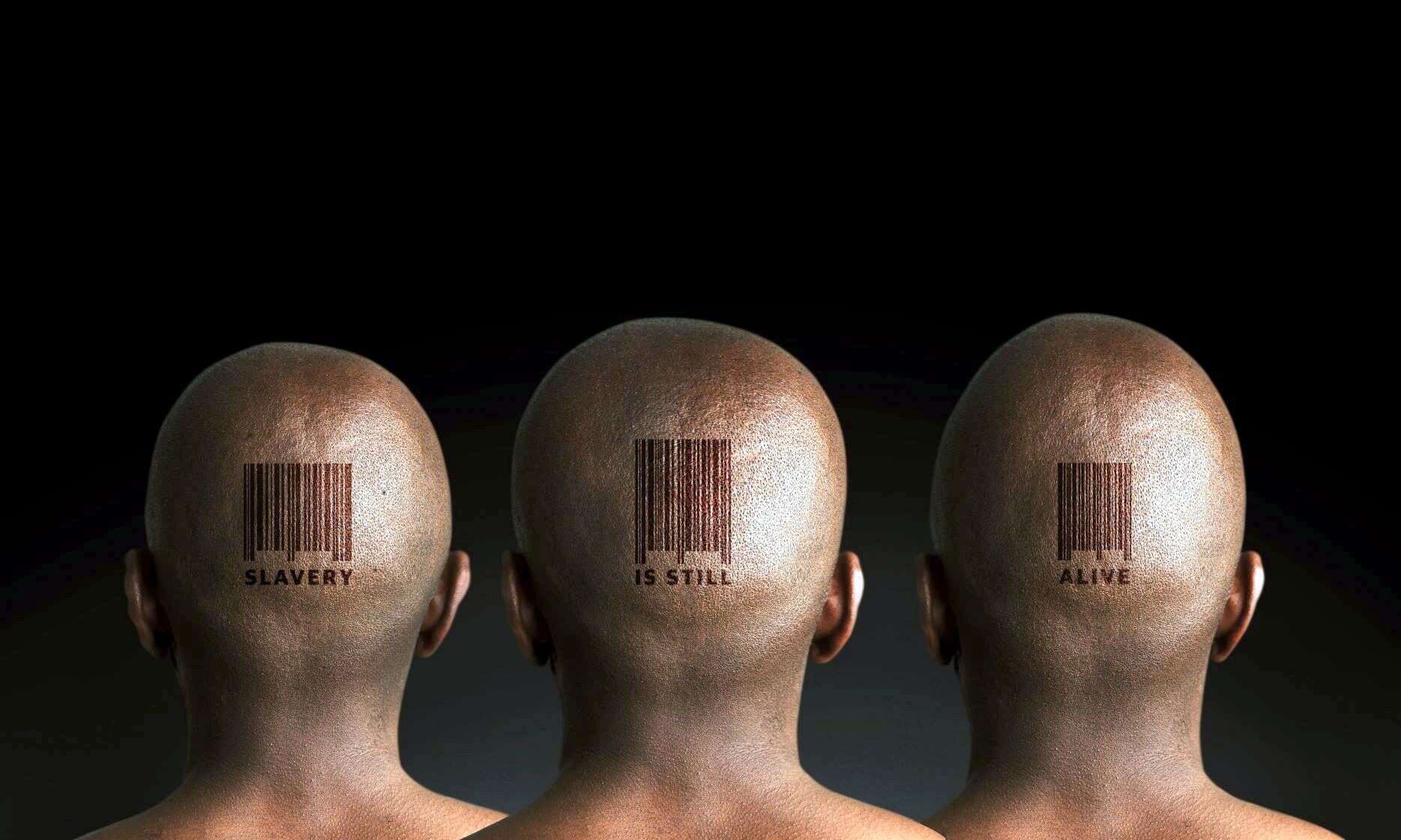

- Since last year Australian portfolio companies have had to report on the risks of modern slavery in business supply chains, but data is scarce.

- So Aware Super, a A$150bn ($108bn) Australian retirement scheme, has developed a tool using data to assess modern slavery risks in its portfolio.

- The fund is also collaborating with investor peers to set out what they expect of companies in this area and identify businesses they should engage with.

It is not easy for companies to find instances of modern slavery in their supply chains, let alone root them out. Many are not willing even to admit that the issue might exist within their operations. Unfortunately, this kind of head-in-the-sand approach can also extend to the fund managers that hold stakes in said corporates. This is something that Australia’s second-biggest pension scheme knows all too well.

Like other asset owners in Australia, Aware Super must report on how it is assessing the risk of modern slavery within its A$150bn ($108bn) investment portfolio, under legislation enacted in 2018.

To that end, it has built a modern slavery risk-assessment tool and started deploying it last year. It requests information such as which jurisdictions and sectors asset managers invest in and whether they assess risks to people within the supply chains of their portfolio companies.

Troubling responses

“We’ve had to look at over 100 fund managers across all our asset classes globally,” Liza McDonald, head of responsible investments at Aware Super, tells Capital Monitor. “Some of our US private equity fund managers responded with: ‘We’re not completing your survey. We only invest in American companies; we don’t have any supply chain or modern slavery risks.’”

The fund houses in question are presumably not aware – or prefer to ignore the fact – that modern slavery is not just an ‘emerging markets problem’. Apple, Gap and Nike are among 82 household names with supply chains “tainted” by the use of forced Uighur labour in China, according to a report published in March last year by the Australian Strategic Policy Institute.

But McDonald has also received far more encouraging responses to its requests.

Aware Super raised concerns about potential supply chain risks at Starbucks with Artisan Partners, a US-based asset manager with holdings in the coffee giant. The company “was keen to be educated and know more about our expectations as an asset owner of them”, she says.

“We have one investment mandate with [Artisan],” adds McDonald. “I thought I was going to be talking to our portfolio manager there and maybe some of the team. But I ended up getting the entire Artisan Partners growth equity team and the firm’s executive management team. Almost 30 people from Artisan were on the call, all wanting to know more. That’s the kind of relationship we want with our fund managers.”

Admittedly, listed companies tend to be more transparent as they face reporting obligations that their private counterparts do not. But private market investment managers will receive more and more such requests for information from institutional clients, especially public sector ones. It seems unlikely they will be able to dismiss them summarily for much longer.

Pressure rising

Regulatory pressure is growing on both asset managers and owners – and the companies they invest in – to disclose more about modern slavery risks to their businesses and penalise those that do not comply. Australia passed its Modern Slavery Act in 2018 after the UK had enacted its law in 2015. Canada looks set to do likewise.

Not before time, as Covid-19 has intensified the risks of modern slavery, thanks to the rise of remote working, national lockdowns and the inability to travel. Investigations, prosecutions and punishments of modern slavery have been disrupted or delayed during the pandemic, according to a June report by UK-based Minority Rights Group and its partners.

But it can take years for legislation to yield the desired results. In the UK, companies have been slow to act despite the law being in place for several years. At least 3,000 of those that should be filing an annual slavery report (those with annual turnover of at least £36m) had not done so as of May this year.

Likewise, there is some way to go in Australia, shows a report published last month by the Australian Council of Superannuation Investors (Acsi). The research was based on disclosure by 151 ASX200-listed companies for the first reporting cycle under the Modern Slavery Act 2018, which ran from 1 July 2019 to 30 June 2020.

The quality of disclosure was low and there was significant room for improvement. The report rated ASX200 statements out of 41, against 41 quality indicators and eight legal compliance indicators. The average score was just 15.4, no company scored more than 30, and longer statements tended to score higher (see graphs below). Moreover, only 5% of companies clearly articulated how they may be involved in modern slavery risks according to the terms set out in the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights.

While it’s now a legal requirement for every Australian company with at least A$100m in annual revenue to produce a modern slavery statement, this is a new concept for most businesses, says McDonald. Even the term ‘modern slavery’ (effectively, enforced employment) is not well understood, she adds.

“But at least we are at a point in Australia where we're able to have those discussions with companies because there's now a legal obligation for them to do something,” McDonald says. That said, the fund does not want companies to see this as a ‘tick the box’ exercise and expects them to do more than merely comply.

New solution

To obtain relevant data on listed companies, the fund worked with Institutional Shareholder Services (ISS), its current provider of ESG data. There was no off-the-shelf solution for assessing modern slavery risks, McDonald says, and the data already available was not specific enough to give a good indication of which companies were more at risk of potential incidents of modern slavery in their supply chains.

So Aware Super asked ISS to support it in screening portfolio companies for such risks. This was one input into the fund’s engagement process, McDonald says.

Having already cut portfolio carbon emissions ahead of its own robust targets (by 45% in its listed equity portfolio since end 2019, for instance), it is now taking a leadership role on certain social issues within investing.

Aware Super started out by considering some of the existing relevant data points, such as whether a company has a policy that supports the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, McDonald says.

Aware Super's tool offers leading indicators of potential risks of modern slavery, such as whether a company has experienced controversy around workers’ rights.

“But what we actually really needed to know was: where are the companies' business operations? Are they in countries where there's more risk to people? Are they in high-risk sectors?”

Then once the data was in, there came the question of how to use it, she adds, such as how to rate the companies and what methodology to use.

One component of the tool is that it offers leading indicators of potential risks. “For example, are there controversies around workers’ rights? We might pick up [from research and media reports] that a company in the portfolio has had ten controversies in the last year around workforce unions, labour rights, those types of things.”

When modern slavery is detected

If Aware Super uncovers incidences or risks of modern slavery, it aims to work with the companies involved to change their behaviour, says McDonald. The fund has come across companies taking passports from workers, for instance.

“If you walk away [by selling your stake], you don’t change any outcomes," she adds. "It’s about the remediation. Can you get that supplier to improve their practices and change what they're doing and get that into contractual obligations with them?”

Aware Super has identified certain sectors at higher risk of modern slavery, such as the electronics industry, because of its sourcing of raw materials, and real estate, notably in how it employs cleaners. Textiles and farming also demand particular consideration.

But the fund knows it cannot address the scourge of modern slavery alone. It has collaborated with others in the industry to establish a group for the Asia-Pacific region called Investors Against Slavery and Trafficking. The group has created a statement about investor expectations of companies around their supply chains and modern slavery risks and aims to identify companies to engage with on such issues. The work is based on charity fund manager CCLA’s ‘Find it, Fix it, Prevent it’ framework in the UK.

“Under this collaboration, all the investors are bringing different data points and sources,” says McDonald. “We’re engaging with NGOs and organisations that audit and assess companies’ supply chains.”

The more light that investors can shine into the murky world of modern slavery, the more such practices will be recognised and rejected. Can it be wiped out entirely? Perhaps not, but the efforts being made by Aware Super and its peers and partners are to be applauded.