- Major US and Canadian retirement funds, including Calstrs and OTPP, are pushing for more certainty on environmental policy.

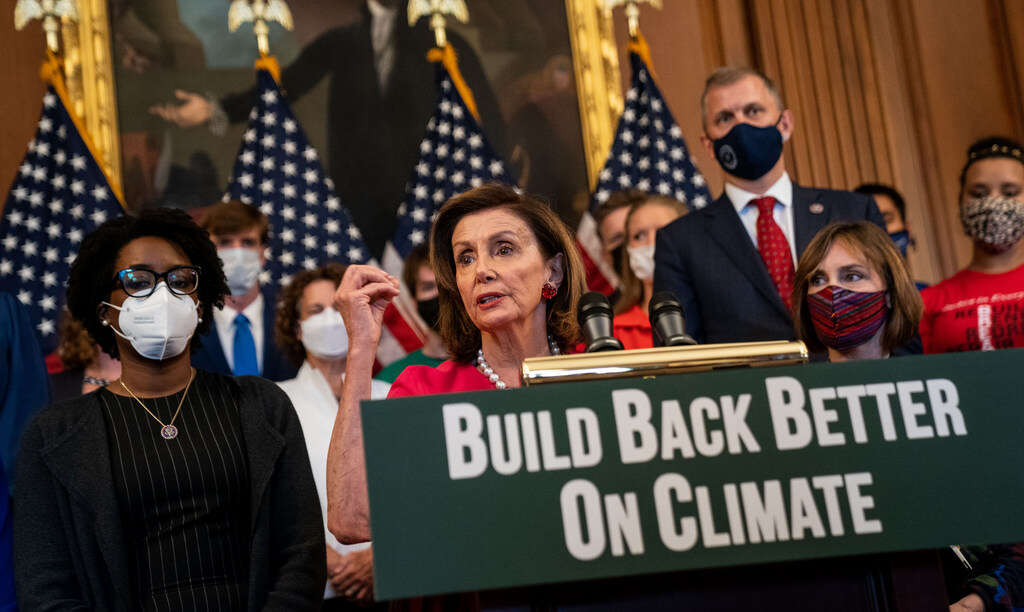

- The US Congress is divided over climate and infrastructure proposals and lobbying against the legislation, including by the financial sector.

- Hence some funds recognise the need to push on with emissions-reduction strategies regardless of regulatory action.

Some of the biggest pension funds in North America are appealing to governments for more policy certainty on issues such as carbon pricing and reporting. But the current impasse in Washington over climate and infrastructure legislation underlines that such ambitions will not be easily achieved.

President Joe Biden’s planned $1trn infrastructure bill passed in August with unusually strong bipartisan support. But progressive Democrats have said they will oppose the legislation without a deal to advance a separate $3.5trn social and climate policy package. As a result, the infrastructure bill could be put on hold for weeks, if not months.

The bills would form a key plank in Washington’s plan – unveiled in April – to achieve a 50–52% reduction from 2005 levels in net greenhouse gas pollution in 2030 and to reach net-zero emissions by 2050. In the same month Biden set out his 2022 budget, incorporating $36bn in explicit climate-focused investment (see chart below), a $14bn rise from this year’s figure.

Hence the impasse in Congress does not bode well for Cop26, a meeting of world leaders to discuss global action on climate change set to take place next month in Glasgow. The event is already beset by fears that it will fail to achieve the aims of the Paris Agreement.

Against this backdrop, some of the world’s biggest long-term institutional investors are pushing for stability on climate policy in the US and elsewhere.

Senior executives from California State Teachers’ Retirement System (Calstrs) and Canada’s Ontario Teachers’ Pension Plan (OTPP) praise Biden’s plans to introduce mandatory corporate climate disclosure, for instance. But they want to see certainty on other environmental issues, such as carbon pricing, to help in their investment decision-making.

Beyond the election cycle

Kirsty Jenkinson, director of sustainability and stewardship at Calstrs, said at a recent event: “We have tried very carefully as a global investor not to just be bound up in the election cycle here in the US to determine what our strategy should be around [carbon emissions] because [the landscape] clearly is volatile.

“We recognise that from a federal level policy could change again in a couple of years,” Jenkinson said during a panel discussion at last month's 'Making Sense of Net Zero' event hosted by Capital Monitor and the New Statesman.

That being said, she added: “I honestly feel, having looked at this kind of area for 20 years in my investment career, we're at a stage of greater certainty than we've ever had before.”

The Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) has moved fast to push for mandatory carbon reporting by corporates, Jenkinson noted. “We are extremely supportive of that. We wrote a very long letter [on] the importance of the SEC setting those ground rules within the US, and hopefully in a way that will be resilient for the long term.”

Calstrs needs to take a longer-term view that goes beyond election cycles and near-term fluctuations. Kirsty Jenkinson, Calstrs

So while Calstrs needs to track domestic and global policy, she added, the $311bn fund recognised the need “to take a longer-term view that goes beyond election cycles and near-term fluctuations”.

Accordingly, for instance, Calstrs on 1 September committed to reaching net-zero portfolio emissions by 2050 and has started gathering the relevant data and planning as to how it will reshape its portfolio to achieve that goal.

Similarly, OTPP has been engaging with regulators around corporate climate disclosures, said Deborah Ng, head of responsible investing at the C$221bn ($174bn) fund. She was speaking on a panel at the Sustainable Investment Forum North America in September.

“If companies are not measuring their Scope 1 and 2 and material Scope 3 emissions, they certainly aren't managing them,” Ng added. “So it's an important dialogue to be had with regulators.”

She said OTPP had been working with groups such as the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board – which has now merged with the International Integrated Reporting Council to form the Value Reporting Foundation – to push for better corporate reporting.

“We've had conversations with and sent letters to the SEC on their work right now in terms of looking at ESG disclosures,” Ng added, “and of course… with our Canadian Securities Association and other groups.”

OTPP in mid-September further underlined its seriousness on the issue by setting ambitious interim targets – to reduce its portfolio carbon emissions by 45% by 2025 and two-thirds (67%) by 2030, compared with its 2019 baseline. These cover all the fund’s assets across public and private markets and include its holdings with external managers.

OTPP calls for carbon pricing

Like other investors, Ng sees carbon pricing as a key area for policymakers to address, if asset owners are to be able to invest with confidence in the technologies needed to help economies decarbonise.

To make such technologies cost-effective “we need to hit a critical mass on investment on technologies”, said Ng. “And that can be supported through things like a tax or a price on carbon.

“Where climate policy and [a] carbon tax play a role is in facilitating the right signals for us to be able to make long-term decisions, [such as on] how viable is hydrogen going to be? What about carbon capture and storage?

“The important thing for Ontario Teachers’ really is having that stable policy,” Ng added. “We need to be able to make a decision that's going to impact our assets over the next 10, 20, 30 years because we have a very long horizon. Especially if you think about our infrastructure assets that we're going to be holding, probably for life.”

Institutional investors have a huge role to play in better aligning capital with sustainable development, agreed Marc-André Blanchard, who oversees C$390bn Canadian pension fund CDPQ’s non-domestic operations. He was also speaking at last month's Sustainable Investment Forum North America.

To meet some of the targets of the Paris Agreement and the Sustainable Development Goals, “we need to double the share of global energy supply from renewables in the coming years”, Blanchard said. That means raising the 26% of energy that is generated from renewables to more like 60% by 2030.

If they are to provide the required capital, investors will, among other things, need “regulatory stability and predictability”, he added.

Bank opposition to Biden's plans

However, reaching policy agreement – in the US at least – on such issues is far easier said than done. There is plenty of opposition to carbon-reduction measures, not least from the banking sector, suggests Ivan Frishberg, director of impact policy at Amalgamated Bank, a union-owned group.

Speaking at the same event as Blanchard and Ng, he said: “Decarbonising the power sector, transportation and real estate all requires real economy policy.” But in a politically divided environment in the US, some large financial institutions – including some in the Net Zero Banking Alliance – are “lining up on the wrong side”.

“There are broad trade groups here – the Chamber of Commerce, [with] their clients in the fossil fuel sectors – who are lobbying and pushing very hard to defeat this legislation. And that is where most of the financial industry is aligned.”

As a result, Frishberg said, there will need to be “dramatic changes in the next few weeks to be able to actually deliver what we want to deliver to [the Cop26 meeting in] Glasgow”.

It is perhaps no surprise, then, that there is so much doubt over what policymakers can achieve there – and why institutional investors are increasingly taking it upon themselves to push the climate agenda.