- Sacha Sadan of the Financial Conduct Authority said in mid-May that regulation of ESG rating providers was coming “quite quickly”; meanwhile, further information is expected in late June.

- Regulating ESG ratings will not be an easy task for financial watchdogs, as such scores are far trickier to calculate than credit ratings.

- It is high time this happens, say some market participants, as these providers wield enormous influence, but certain rating agencies are pushing back.

The topic of ESG ratings, and their place within sustainable investing, invariably prompts lively debate. One oft-raised question – whether this area will be regulated – appears to have been settled, at least from the perspective of the UK’s Financial Conduct Authority (FCA). Speaking at the Financial Times’s Moral Money Summit in London last week, the FCA’s ESG director, Sacha Sadan, said regulatory oversight of ESG rating providers “is coming, and coming quite quickly”.

That will come as welcome news to investors and other groups seeking more transparency over such providers’ methodologies and mitigation of potential conduct risks. After all they wield major influence in that they analyse public information to grade companies and sort them into ESG indexes.

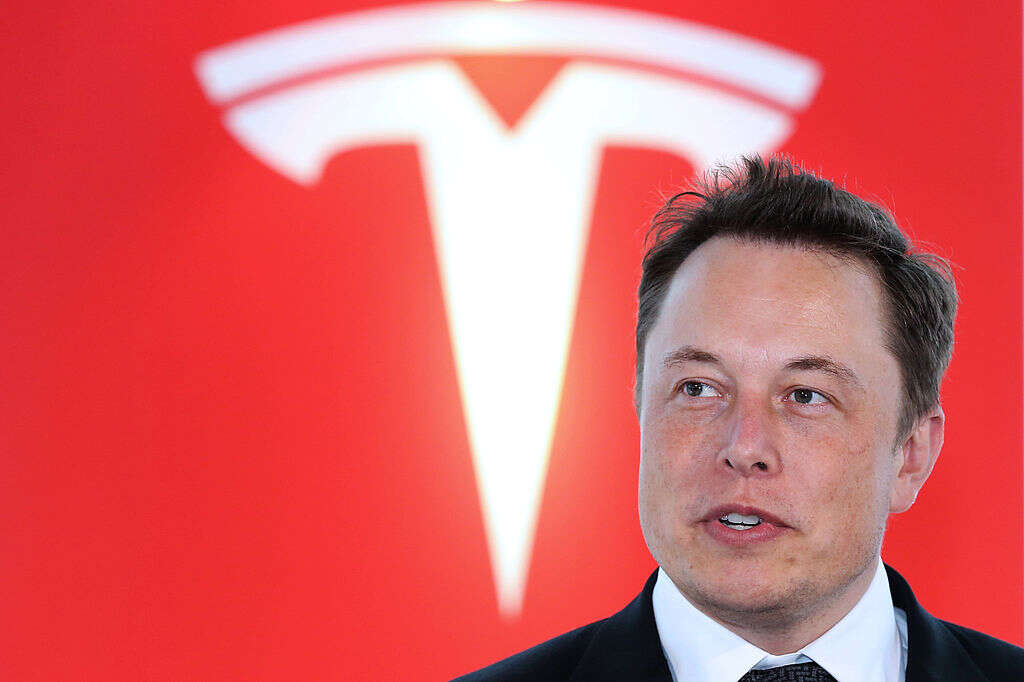

Just last week there were renewed calls for action after it emerged that Standard & Poor’s had removed electric vehicle manufacturer Tesla from its S&P 500 ESG Index – much to Elon Musk’s disgust – but retained the mega-polluting oil firm ExxonMobil, which is frequently ranked as the most obstructive company in respect of climate policy progress. The rating agency cited incidences of racial discrimination and poor working conditions at Tesla as its rationale for the decision.

Instances such as this underline both the influence at ESG rating providers’ disposal and the challenges of trying to include such disparate themes as environmental and social factors – that might cover anything from tackling deforestation to modern slavery risks in supply chains – within one neat scoring system.

The latter also helps explain why there is such a wide disparity between how companies are rated. MSCI gives Tesla an ‘A’ rating, Sustainalytics ranks it 28.5 – denoting medium risk (negligible being 0-10 and severe being 40-plus) – and Refinitiv gives it 63 out of 100.

Commenting on the Tesla exclusion, Sadan said: “Does anyone think there is one number out there that tells a company whether it’s good or bad? They might be good at some things and bad at other things.”

Rising up the agenda

Providers of ESG data and ratings have been on regulators’ radar for some time and recently moved up the priority list. The UK government said in its 'Greening Finance' roadmap in October that it was considering bringing the sector under the FCA’s purview.

Sadan said regulators, including the FCA, International Organization of Securities Commissions (Iosco) and the European Securities and Markets Authority (Esma), were considering points such as: the weighting of different ESG considerations in ratings; what companies are doing on health and safety; how investors can be sure the rating is verifiable; and how agencies manage conflicts of interest.

Some rating agencies have said they would welcome “guard rails” while others do not think they need to be regulated, Sadan added. “Well, they may not think so, but that is the passage that is coming, and it’s coming quite quickly.”

There is “active dialogue” between the FCA and HM Treasury on this area, well-placed sources tell Capital Monitor. They also say the FCA will publish a feedback statement on capital market ESG issues, including the future for the ESG data industry, in late June. An FCA spokeswoman declined to comment.

Seeking transparency

The regulator appears to have the data to back up its position. There are dozens of academic papers highlighting major discrepancies in ESG measurements and data quality problems. With trillions of dollars flowing into sustainable funds, indices and products every year, many of those investment decisions are based on data and analysis provided by companies that refuse to show how they come to their conclusions.

“Different data may lead to different assessments of similar or the same companies, and that might be fine, but we need to understand why these differences exist,” Paul Tang, a Dutch politician and member of the European Parliament, tells Capital Monitor. “I’m also concerned about whether [these service providers] are independent. But the starting point is them being more open on the methodologies they use.”

This is why some institutional investors prefer not to rely on third-party ESG ratings and have instead developed their own rating and scoring systems. That is an approach taken by Japanese insurance company Nippon Life and Spanish insurer Mapfre, as Capital Monitor has reported. Similarly, Norges Bank Investment Management, which runs Norway’s $1.4trn sovereign wealth fund, tends to dig into the underlying data rather than look at ESG ratings to help inform its allocation decisions.

But not everyone has the resources to handle things internally. “Are we really comfortable with such an important market being outside of the regulatory sphere, and this data being used for investment decisions?” asks Raoul Kohler, senior policy adviser and sustainable finance coordinator at the Netherlands Authority for Financial Markets.

Rating providers’ response

On the whole, data providers acknowledge their growing influence and the need to provide more transparency. But not all are so supportive of regulatory reach. Andrew Steel, head of Sustainable Fitch in London, says it does not make sense to regulate ESG ratings: “The question arises as to what exactly regulators would regulate.”

Given the nature of ESG scores and ratings, he adds, the best approach would be to create “an international code of conduct laying out consistent standards”. It would be based around the core concepts of transparency and consistency of application of methodology, says Steel, as well as the management of potential conflicts of interest, integrity of analysts, the protection of confidential information, and so forth.

While the often-wild variations in ESG scores put some investors off, most agree that diversity of opinion is important. The number one consideration for regulators should be ascertaining exactly what purpose an ESG rating or score is seeking to serve.

“The methodology for our final output scores is proprietary, and that is where the difference lies between providers and the different scores they get,” says Georgina Symons-Jones, London-based commercialisation director at ESG data provider Sustainalytics. Nonetheless, she adds that the company is well positioned for future regulation.

“One of the key problems is that every single rating is measuring different things – we’re never going to have a perfectly comparable market [as] we do with credit,” says Kelly Sporn, London-based senior ESG policy adviser at law firm Allen & Overy.

“At the same time, there are concerns about the influence of these ratings because of how broadly they’re being used – not just for investment purposes, but also by companies to benchmark their own performance.”

Europe and beyond

The European Commission first introduced the concept of regulating ESG data and benchmark providers in its game-changing sustainable finance action plan in March 2018.

Subsequently, in a report in November last year, Iosco raised concerns about the lack of transparency around how ESG rating and data products were put together and over potential conflicts of interest within rating providers. Iosco recommends that regulators pay more attention to such groups’ activities.

As per Iosco’s recommendation, there are two main prongs that regulators would likely pursue in their oversight: transparency of methodologies and disclosure of potential conflicts of interest. Another key focus is improving the quality of self-reported corporate disclosures – as is happening from the UK to the US to New Zealand – which should reduce discrepancies across the board, says the UK Sustainable Investment and Finance Association. The association also suggests regulators provide guidance for investors and others on how to use third-party ESG data.

India could be among the first countries to regulate the sector, after the Securities and Exchange Board of India launched a consultation in January proposing that ESG rating agencies apply for regulatory accreditation and disclose their sources.

Meanwhile, Illiani Lani, head of ratings, indices and securitisation at Esma, endorsed Iosco’s recommendations, calling for regulation to ensure the integrity and reliability of ESG ratings while still allowing them to be flexible and have objective measurements. In February, Esma launched a call for evidence on the subject.

Yet it is entirely likely that the EU will take a different approach from other jurisdictions, Sporn says.

As ever, regulatory harmonisation may be a long time coming – if it comes at all – but investors will be glad that the process has finally begun for ESG ratings.