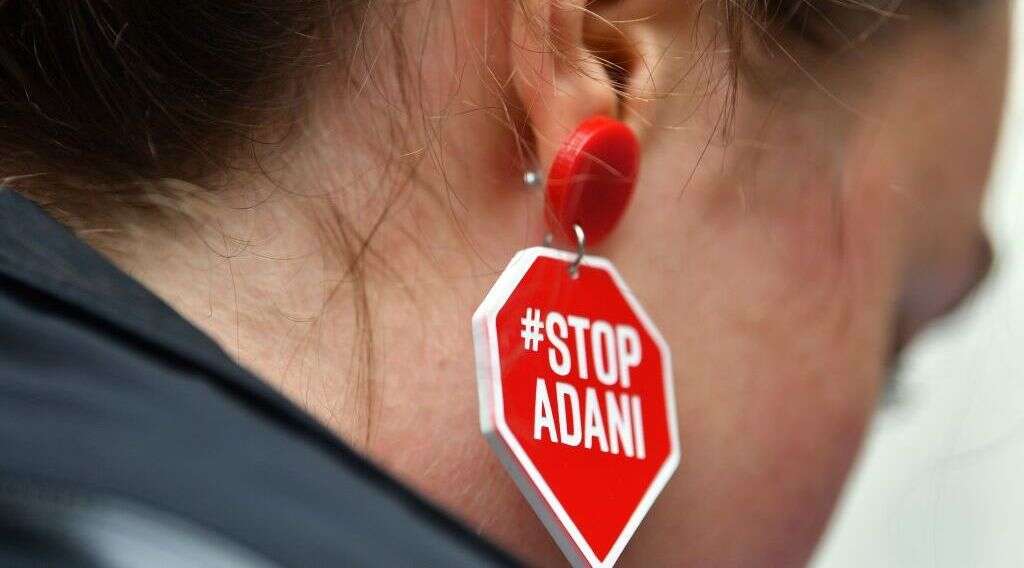

Adani Group has become a lightning rod for public criticism of coal power. (Photo by Saeed Khan/AFP via Getty Images)

- Adani Group, the world’s largest private developer of fossil fuels, is under pressure to live up to its much-trumpeted sustainability claims.

- Despite steadily growing opposition to Adani’s activities, the group is having little problems raising cash, and shares in its companies soared last year.

- Carbon Tracker estimates that Adani Group’s assets have a stranding risk of $12bn, or 45% of its market capitalisation.

The weight of money and opinion turning against coal as a power source appears, on the face of it, overwhelming. India’s much-criticised Adani Group – incorporating both coal and renewable energy in its activities – has become a lightning rod for this debate, encapsulating the dilemma that fossil fuel assets pose to investors.

At November’s Cop26 climate talks in Glasgow, another 28 members joined the Powering Past Coal Alliance, with Chile and Singapore, among others, joining some 160 countries, regions and businesses as part of the world’s largest group focused on phasing out the commodity.

This could shift an estimated $17.8bn a year in public support out of fossil fuels and into the clean energy transition.

“Securing a 190-strong coalition to phase out coal power and end support for new coal power plants [along with] the Just Transition Declaration signed today show a real international commitment to not leave any nation behind,” said a jubilant Cop26 president, Alok Sharma, on 4 November.

However, certain countries did not sign up – notably the US, China, India and Australia. Given their huge reliance on coal mining and/or generation – the commodity remains the biggest source of power for both China and India, for instance – their absence leaves a gaping hole in the size of commitment required to achieve net-zero emissions globally.

Gautam Adani, chairman of the Adani Group, regularly touts his firm’s green credentials. (Photo by Sanjeev Verma/Hindustan Times via Getty Images)

And while China has pledged to stop financing coal overseas, India continues to do so. At the forefront of the country’s activity in this area is Ahmedabad-based multinational Adani.

“What I can categorically say is that Gautam Adani [the company’s chairman] is the biggest private developer of fossil fuels in the world,” Tim Buckley, director of energy finance studies for Australasia at the Institute for Energy Economics & Financial Analysis (IEEFA) in Sydney, tells Capital Monitor.

Widespread frustration

Founded in 1988 as a commodity trading business, Adani engenders widespread frustration that is perhaps understandable. The group is widely seen to be playing down its emphasis on coal via corporate sleight of hand while promoting itself as a sustainability champion. And it is – for the time being – coping comfortably with a growing number of major institutions withdrawing funding and increasingly negative sentiment generally from investors, financiers and the public.

Over the past six months investors have hoovered up international bonds issued by the group. Adani Green Energy sold a $750m 4.375% three-year green bond in September, Adani Ports and Special Economic Zone raised a $750m two tranche 10.5-year and 20-year bond in July, and that same month Adani Electricity Mumbai printed a $300m ten-year 3.865% sustainability-linked bond.

The issues are holding up well. Adani Green Energy’s 2024-maturity debt was trading at 101.50 early January, Adani Ports’ $300m 2032 issues at 98.2 and Adani Ports’ $450m 5% 2041 bonds at 102.48. The company has even signed a $1.35bn green four-year revolving credit facility, the largest loan in India’s renewables sector, to finance the construction of four solar and wind projects in Rajasthan.

What’s more, Adani Group’s units listed on the BSE (formerly the Bombay Stock Exchange) in Mumbai are enjoying soaring stock prices. Last year, shares in Adani Power returned 97%, Adani Enterprises was up 249% and Adani Transmission gained 289%.

Public capital markets are clearly financing thermal coal, says David McNeil, head of climate risk at Fitch Ratings in London. “Developers of new projects can get access to finance without too much difficulty.”

Touting green credentials

To be sure, the group does have a substantial renewables business, which Adani – Asia’s second-richest man, with a net worth of $78.3bn, according to the Bloomberg Billionaires Index – is a dab hand at marketing. He constantly touts his green credentials.

The company, which declined to comment for this article, was the main sponsor of Dubai’s TiE Sustainability Summit in October last year. Adani said at the event: “The task before us is not just to find a solution to climate change, but also to ensure – through science, policy and technological development – that the principles of equitability are not ignored.”

That same month, he tweeted about “power[ing the] future through low-carbon technologies”, and after meeting British prime minister Boris Johnson that month he talked about “inspiring leadership in synchronising global climate action”. And he regularly raises the themes of solar power and doing social good.

The Adani Group operates as a conglomerate, but, when convenient, it uses its structure to greenwash certain parts. Pablo Brait, Market Forces

Meanwhile, in Adani’s ESG report from March last year, the only mention of coal is historic, with the assertion that it has “evolved from a coal trading house to a sustainable infrastructure owner”. Moreover, there is no obvious mention of coal on the Adani Group website, nor is it mentioned in the company organisation chart.

But the importance of coal to the company cannot be underestimated, though it is hard to obtain precise figures, as they have not been fully disclosed for the past few years. In the 2019 financial year the volume of coal mined by Adani Enterprises grew 72% to 12.1 million metric tonnes. Adani Ports reported that its coal cargo volumes rose 8.3% in 2021 to 78 million metric tonnes.

Moreover, Anil Sardana, managing director of Adani Power, the largest private thermal power producer in India, said at the release of the group’s second-quarter results in October last year: “Coal power continues to be a requirement for economic growth with a reliable and cost-effective power supply.”

Adani is developing 110 million tonnes per annum of new Indian coal mine capacity and 9GW of new coal-fired power plants, on top of several liquefied natural gas (LNG) import terminals, a $4bn imported coal-to-PVC proposal and new gas reticulation systems throughout India.

Hence there is a real threat that many of Adani’s assets will end up distressed. An estimated $12bn of the group’s assets – or 45% of its market capitalisation – are at risk of becoming stranded under a beyond 2°C scenario, according to a November report from London-based think tank Carbon Tracker (see chart below).

Carmichael the main bugbear

Opposition to Adani’s activities has crystallised around its Carmichael thermal coal project, which is tapping a previously untouched coal basin in Queensland, Australia.

Adani has created “a foothold” in the Galilee Basin, says Pablo Brait, a campaigner for Australian non-profit research organisation Market Forces. “It is crucial, globally, that the Galilee Basin carbon bomb does not explode into the atmosphere,” he adds.

The project exported its first coal eight years later than scheduled at the very end of 2021. Financing the project was a challenge, Brait says. Adani has had to use its own money to fund the development of the Carmichael project, “which is rare”, he says.

A growing number of large companies have been publicly withdrawing or ruling out support.

Deutsche Bank walked away from involvement in the $500m 3.1% ten-year bond sale by Adani Ports and Special Economic Zone at the start of last year after concerns were raised by its sustainability committee. Copenhagen-based Danske Bank has restricted investment in all Adani companies for their exposure to coal and contributions to climate change.

Asset managers and owners have made similar moves. State Street put both Adani Enterprises and Adani Ports on its ESG exclusion list, after Dutch insurance and investment company NN Group had done the same in March. Swedish pension fund SPP did likewise in March for Adani Ports, citing “serious environmental and climate damage”. In the same month, US-based $2.2trn fund house Pimco ruled out new investment in Adani Ports bonds.

Index providers have been following suit. In November, MSCI removed Adani Ports from four of its climate change benchmarks. Rival S&P had already removed the company from its sustainability index in April as a result of its business ties with Myanmar’s military dictatorship. Adani Ports had planned to build a $290m port in Yangon, which was leased from the army-backed Myanmar Economic Corporation. The company scrapped plans to build the container terminal at the end of October.

The Carmichael project is also finding insurers harder to come by. In November, the UK's RSA and Conduit became the 41st and 42nd insurance companies to rule out underwriting for the project, reflecting a wider trend.

As of November, 35 insurers had withdrawn cover from coal, up from 23 a year earlier, including at least 50% of the global reinsurance market, according to Insure Our Future, a London-based global network of NGOs and social movements calling for insurance companies to divest from and stop insuring coal.

Adani Group regularly responds to media criticism either via its own website or via the stock exchange. For instance, in a statement to the BSE after the MSCI climate change benchmarks decision, Adani Ports said the move appeared to be “playing right into the hands of forces that want to subvert the green initiatives to which the Adani Group has made massive public commitments and tarnish the reputation of one of the leading green port operators of the world”.

Adani Ports added that it had divested its controversial stakes in both deepwater coal port NQXT (North Queensland Export Terminal) and Bowen Rail Company in Queensland, set up to transport coal from the Carmichael mine to NQXT.

Be that as it may, the two companies remain wholly owned by the group. NQXT is part of Adani’s transport and logistics portfolio, and the group transferred ownership of Bowen Rail from Adani Ports to Adani Enterprises in 2020. Adani Ports said in its 2020 annual report that it had made the transfer to fulfil its “carbon-neutral commitments”.

“The Adani group operates as a conglomerate, but, when convenient, it uses its structure to greenwash certain parts, to shift dirty businesses to one part while committing to carbon neutrality for other parts,” says Brait.

Private equity still in support

Despite the waning support for Adani in some quarters, there are still plenty of places prepared to provide funding. US fund house BlackRock has an estimated cumulative exposure to the group of $1.2bn in debt and equity, according to a report from the IEEFA. The asset manager’s argument is that much of this investment is passive, but this as an excuse, says the IEEFA's Buckley. “BlackRock is still the biggest investor in the Adani Group.”

Moreover, private equity firms are still seen to have appetite to invest. “Private equity investors can sidestep some of the kind of pressures that are on public markets either to divest or to reduce the emissions intensity of investments or assets,” says Fitch’s McNeil. Only 16 of the 431 private equity firm signatories to the UN Principles for Responsible Investment disclose impacts of ESG factors on financial returns, said a report from Fitch in May last year.

Luciano Siani Pires, chief financial officer at Brazilian miner group Vale, said on LinkedIn at the start of January: “Precisely because coal-related assets have become toxic for listed companies, private equity firms are hunting thermal coal power plants and coal mining properties across the world at bargain prices, aiming at juicy returns, as they do not have ESG-minded constituencies to attend to.”

When will the tide turn?

The tide is expected to turn against Adani at some point, of course. The question is, when? After all, China and India are forecast to be heavily reliant on coal for some years to come (see pie chart below).

In the meantime, Adani has no obvious exit strategy from coal and is challenging India’s aim of achieving net-zero emissions by 2070. As it is, the company is likely to have to rely on expensive government contracts that a future administration might not honour.

Adani’s critics commonly liken the company to a hydra, the serpent-like monster of Greek mythology whose multiple heads would regenerate and multiply after being cut off.

“Adani Group is a conglomerate growing in all directions,” says Brait. “What we are trying to do is convince the company that it should stop growing in the direction of fossil fuels."

Logic dictates that such persistence will pay off – but it could take a while longer to do so.